Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this week’s edition of 2-2-2, we announce the AI + Energy Summit for September 2024, and SCSP’s Pieter Garicano, Nina Badger, and Nicholas Furst discuss how solving the energy bottleneck will be the key to AI leadership.

Announcing the AI+ Summit Series

SCSP is excited to announce the AI+ Summit Series, a set of high-level events dedicated to enabling rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) as it transforms our country and becomes a keystone of our national security.

The AI + Energy Summit, the first in this series, will take place on September 26, 2024, in Washington, D.C.

As we discuss in this newsletter, realizing advanced AI will require an abundant supply of reliable, resilient, and low-cost energy, which we do not yet possess. The United States cannot win the technological competition without solving the energy bottleneck.

Conversely, emerging technologies, and AI in particular, will play an important role in positioning the United States to lead in the energy transition. AI is already showing promising pathways toward maximizing energy efficiencies, discovering new materials, and enabling new forms of power generation.

This first summit will bring together senior policymakers, energy industry leaders, and prominent technologists to work on the ideas and solutions that will enable America to maintain its competitive edge at the nexus of AI and energy.

AI’s Missing Piece

The United States leads the world in AI. If it doesn’t fix its power problem, it could lose its edge. The proliferation of data centers that power AI, efforts to onshore manufacturing, and rapid electrification driven by decarbonization are putting enormous pressure on utilities as they struggle to meet the necessary demand.

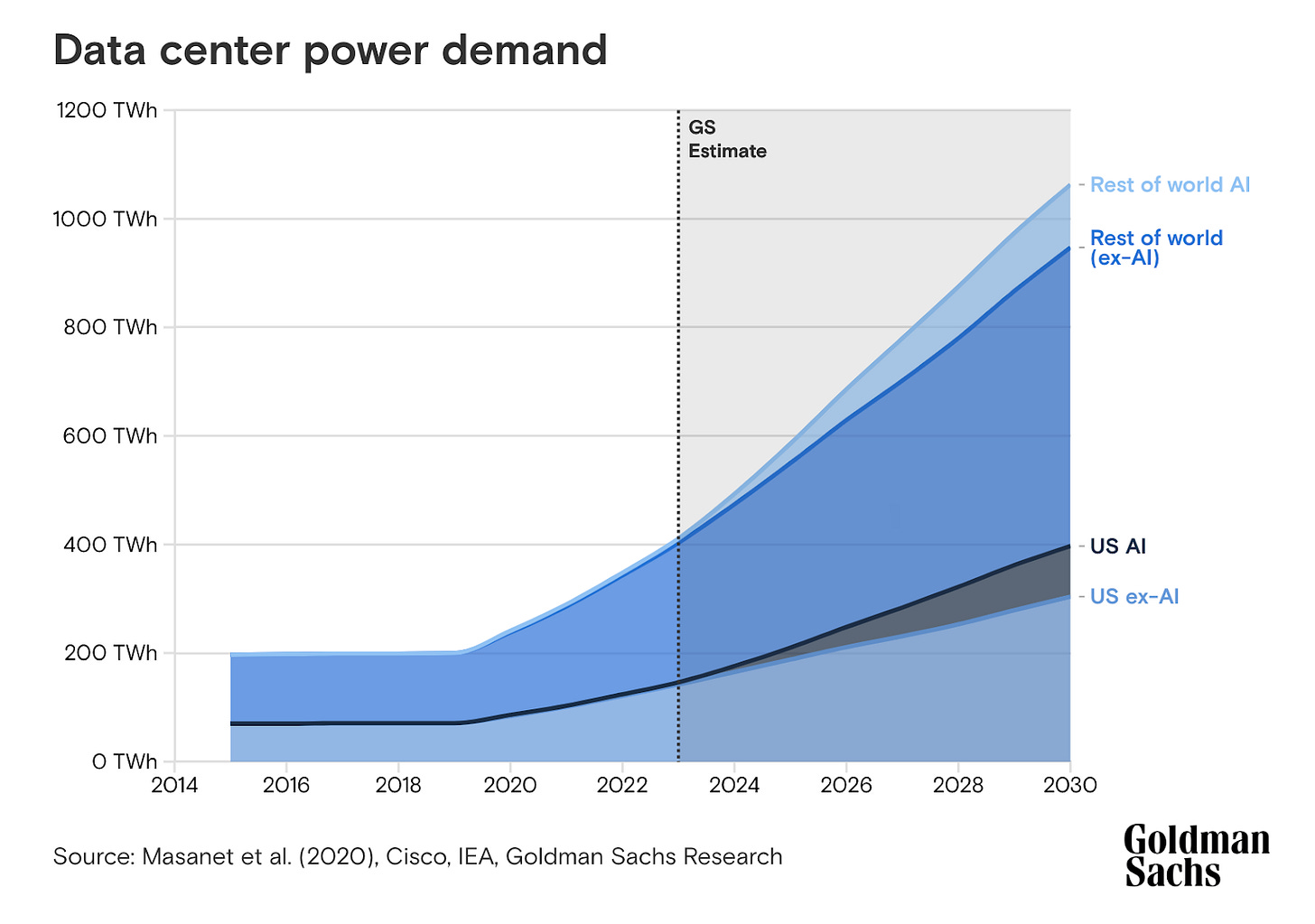

According to one estimate, the growing use of commercial AI models will cause data centers to increase their energy consumption by 160% by 2030. Another estimate indicates that data center operations may grow to over 9% of total annual energy demand in the U.S. by 2030, over twice their current levels.

The energy required by individual leading data centers will increase even more rapidly than the industry at large. The current approach to training and running frontier AI models involves concentrating power at single data centers. If the next generation of models sees an increase in raw computing power similar to the estimated jump from GPT-3 to GPT-4, they would require up to a gigawatt (GW) of power for a single data center — roughly the energy consumed by 750,000 households. A three-order-of-magnitude increase in computing power, no larger than the jump between GPT-2 and GPT-4, would bring us up to 10 GW for a single data center — equivalent to the power capacity of all of Connecticut in 2022.

While those forecasts seem extreme, some are already becoming a reality. In March this year, Amazon spent $650 million on a 960-megawatt data center powered by a nuclear reactor in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. In a recent interview, Mark Zuckerberg stated that it is “only a matter of time” before tech firms would build gigawatt-sized data centers. To believe that the United States would need 10 GW data centers in the next three or four years only requires believing that current expansions of computing power continue to hold. As Leopold Aschenbrenner, formerly of OpenAI, put it in a recent essay, “What any compute guy is thinking about is securing power, land, permitting, and data center construction.”

Despite the urgency of a large-scale power buildout to create new generations of frontier AI models, the United States is currently off-track to meet even the more conservative demand estimates — let alone the likely multi-gigawatt requirements for individual data centers.

The challenge goes beyond sheer energy consumption. Unlike residential energy consumers, data centers require consistent, round-the-clock baseload power. Hydrocarbons may be needed to bridge initial gaps, but they are neither clean nor sustainable. Renewables such as solar and wind are insufficiently reliable (able to provide a consistent supply of power) and dispatchable (able to be used on demand).

When it comes to nuclear, a strong candidate, our current regulatory scheme will be a limiting factor. An illustrative case is that of the Vogtle Nuclear Plant in Georgia, whose third and fourth reactors came online in 2023 and 2024. Each reactor provides 1.1 GW of capacity. Combined, they represent the only reactors constructed this century. The initial permits for these reactors were applied for in 2006 — almost 18 years ago — and construction began more than a decade ago in 2013. The total cost of both reactors came to over $34 billion. With timelines and price tags like this, it is difficult for fission energy projects to meet data center energy demand in the short run.

New energy projects are slow to build out across the country, often in large part because of the protracted planning, siting, and permitting process. Projects may frequently be delayed by litigation, including by claims that energy project developers have violated certain federal or state laws — such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The most frequently litigated projects include renewables like wind and solar, as well as transmission line upgrades.

To build the power needed, the government will have to make serious reforms. SCSP has presented various options to reform the judicial review process to speed up energy infrastructure buildouts, such as reducing the statute of limitations and standing for NEPA claims (to eliminate frivolous litigation) and standing up a federal court with exclusive jurisdiction over permitting cases (to expedite legal proceedings).

Reforms will also need to enable grid modernization, specifically in power transmission. Efficient transmission lines are imperative if power is to get where it needs to go. As it currently stands, the U.S. power grid relies on outdated analog designs. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission should use performance-based incentives to encourage the adoption of grid-enhancing technologies, which would increase transmission capacity and minimize the risk of overloads, among other things.

Yet reforms to transmission lines and other grid infrastructure currently face significant bureaucratic hurdles, despite executive branch support. Transmission line construction has dramatically slowed, with under 1,000 new miles being added in 2021, compared to 4,000 miles in 2013 alone. If efforts to achieve a power buildout in the private and public sectors do not develop in tandem, this misalignment could cause gaps in grid infrastructure.

Technology Solutions

Technology, and AI itself, will play a role in easing some of the energy challenges. In May, in two separate fusion experiments, U.S. and South Korean researchers used machine learning in real-time to reduce the amount of energy escaping from the reaction, improving its efficiency without harming its quality. The Department of Energy (DOE) already uses AI for advanced computing, emergency response, environmental modeling, climate forecasting, materials research, and more. Its efforts range from developing LLMs for nuclear power plant regulatory approval to digitally exploring historical oil and gas drilling records, using machine learning to research hydrogen-based turbine materials, and optimizing integrated hydrogen and power production systems through reinforcement learning.

Elsewhere, advanced energy technologies are leaving the drawing board and becoming a reality. A public-private partnership between TerraPower, a firm founded by Bill Gates, and the DOE Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program recently began construction on a natrium plant earlier this week.

While initial construction is starting, additional regulatory review is required before TerraPower may begin building the nuclear components of the plant. The firm submitted a 3,300-page application to build the nuclear reactor to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in March, with the NRC’s review and approval process expected to take a minimum of two years. Assuming that the process is completed on time, the plant will become operational in 2030.

Recent breakthroughs in fusion energy in national labs across the United States, as well as significant private sector investment in the sector, indicate that this technology may become another useful component of a long-term energy buildout. As fusion progress accelerates, the U.S. government must meet the corresponding need for effective policy.

Fortunately, policymakers are making progress. The White House’s release of the 2024 Department of Energy Fusion Energy Strategy last week is a good first step in this domain. But winning at fusion, as in other domains, will require effective prioritization and organization, as well as resourcing.

Beyond fusion, the House Subcommittee on Energy, Climate, and Grid Security held a recent hearing on data center–driven energy demand growth. The Department of Energy is pushing ahead in a number of domains. It has launched a number of ‘Energy Earthshots,’ as well as reports on the deployment of new energy technologies and efforts to improve the workforce. Internationally, the G7 held a Climate, Energy, and Environment Ministers’ Meeting in April, which culminated in an agreement to work to use artificial intelligence and machine learning tools for “climate, energy and environment decision making.”

These policy recommendations, largely aligned with SCSP’s Next-Generation Energy Action Plan, are a step in the right direction. But the magnitude of power required for new and existing technologies means that we will need moonshots to meet demand in the next few years rather than a decade out, lest we cede AI leadership. They should be accompanied by clear and specific regulatory frameworks that supercharge energy and infrastructure project development.

Getting serious about AI means getting serious about energy. Furnishing data centers with the extraordinary power necessary to keep AI on the cutting edge will require bold but targeted investments in energy. It is no wonder that OpenAI is reportedly seeking to purchase large quantities of fusion energy, following the same move by Microsoft last year. Solar and wind power cannot shoulder so much of this burden, and the easiest alternative to nuclear power is carbon-based fuel — a nonstarter for many.

SCSP’s AI + Energy Summit will organize for solutions. Convening the nation’s top experts to collaborate on energy solutions for AI innovation is a key step toward ensuring our national security and future prosperity. In energy, the U.S. should not compete alone; we will be better positioned to maximize our competitiveness relative to China by fostering close collaboration with our allies and partners on energy supply chain resilience and sensible policy coordination.

Pioneering the development and deployment of AI is necessary for maintaining U.S. global leadership, and investing in data center buildout is a crucial component of achieving this goal. The logistical and environmental challenges these investments pose are best understood as the growing pains of the AI revolution.

In the push for energy abundance for AI, the stakes could not be higher. The United States’ adversaries, particularly China, do well at rapidly scaling up large infrastructure projects. Already, China is the world’s largest power generator. Failing to deliver on energy would hand AI leadership to our adversaries. Power is a missing piece in the technology competition.

يمكن ان يكون للمشكل الواحد اكثر من حل،ولكن في الواقع العملي الذي لايزال غائبا عن إدراكنا العلمي والتقني لن يكون إلا خيارا واحدا وهو الاسمى ،ان ما تتخبط فيه التكنولوجيا اليوم عايد بالاساس إلى هذا القصور ،قصور نكتشفه عمليا ونتدارك تجاوزه بالبحث العلمي ،للارتقاء و التطوير،وهذا ما يمشي على الامن السيبراني ،وان المشكل تقني وآلي وليس امرا في النفس و العقل البشري فإن التحكم في الآلة اسهل ما يكون ،فلا القوانين و لا الأدبيات تستطيع الخد من المعضلة ،ذلك ان العيب في الآلة والتقنية هو منفذ دخول التصرفات والممارسات الغريبة،فالفم المسدود لا يدخله الذباب،لهذا اصدقائي الاعزاء هناك مشكل تقني في العمل على تامين الحقل السيبراني لا اقل ولا اكثر ولن ياتي الخل من مكان اخر،اذا كنتم مستعدين للتعاون ورفع هذا التحدي من اجل عالم مشترك آمن لا تترددوا في اعتماد تقنيات IMm

مع خالص التحيات

OUCHAMCH MUSTAPHA

نعم هناك حلول وفرص يجب ان تستغل ،يجب ان ننصت لبعضنا ،لنتعاون مع بعضنا ،لان المستقبل نتقاسمه كلنا