Does The United States Need a Techno-Industrial Strategy?

Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP). Welcome to the 2-2-2. The 2-2-2 brings you monthly analysis on topics at the intersection of technology and national security.

Save the Date:

Mark your Calendar! On September 16, 2022, we will be hosting our Global Emerging Technology Summit. The purpose of the Summit is to bring together government and private sector leaders from the United States and our staunchest allies and partners to ensure that emerging technologies help advance freedom, strengthen democracies, and protect the rules-based order.

SCSP Call for Engagement:

Our Call for Engagement ends next week on July 29th! Make sure to submit your answer to the question of: “How can the United States and allies and partners better deter authoritarian aggression in the Western Pacific and Eastern Europe?” Specifically:

What low-cost techniques that could be implemented in 2-3 years might strengthen deterrence?

What strategies might the United States pursue that preserve our vital strategic interests more effectively than deterrence?

What does the United States get wrong about deterrence, including its relevance as a concept, how emerging technologies are changing the nature of deterrence, or how different cultures perceive deterrence differently?

From May 2 to July 29, 2022, SCSP will accept submissions in the form of a short paper or video answer to the prompt. Up to 3 entries will be selected to be published in the SCSP Newsletter, 2-2-2, as well as on the SCSP website, and SCSP will offer the authors of the three submissions $2,000 respectively. The authors of the selected submissions may also have an opportunity to brief the SCSP Board of Advisors.

Visit our website to learn more and upload your submission.

Does The United States Need a Techno-Industrial Strategy?

Edition 6

In this month’s edition of 2-2-2, SCSP Economy Panel staff–Senior Director Liza Tobin, Director Warren Wilson; Associate Directors Brady Helwig & Katie Stolarczyk; and Research Analyst Humza Jilani discuss whether the United States needs a technology-focused industrial strategy.

What role should the government play in spurring America’s international technology competitiveness? For some, the answer is “no role at all.” But throughout American history, targeted government intervention has helped the nation prepare for major wars, build world-leading infrastructure, and maintain technological advantage. At the height of the Cold War, for example, President John F. Kennedy set a national goal to land a man on the moon within the decade. Not only did this ambitious mission succeed, but guaranteed demand from NASA and the Defense Department jumpstarted the microelectronics industry. American industrial strategy put Silicon Valley on the map.

As democracies wake to the growing techno-economic competition with China, Washington and other capitals are turning to industrial strategy to boost competitiveness in emerging technologies. The White House has called for a “Modern American Industrial Strategy” to help the United States build manufacturing capacity for critical inputs. Congress is also considering the CHIPS Act, which would provide incentives to increase R&D and domestic production capacity for semiconductors. Industrial strategy is not central planning—instead, it involves government intervention to stoke innovation and help companies compete in targeted sectors considered essential for economic and national security.

An industrial strategy that places technology at the center can accomplish two objectives:

Fill national and economic security gaps. Decades of outsourcing have contributed to the “hollowing out” of America’s industrial base. Today, the United States has limited production of critical technology inputs like microelectronics, advanced batteries, and rare earth minerals. These vulnerabilities have left the nation exposed to supply shocks and shortages of military supplies. A technology-focused industrial strategy could incentivize the return of manufacturing critical to economic and national security.

Grow the pie. Technology-focused industrial strategy can boost economic output, increasing American prosperity and economic power. Developing new technologies and scaling them is the clearest path to generate national wealth. Ultimately, the U.S. government can boost economic output by stoking innovation and paving the way for technology to diffuse across the economy. Investing in America’s workforce and technology infrastructure can unleash innovation and economic growth. Stronger economic foundations translate into better livelihoods for American workers and more resources to build a nation’s military, pursue foreign policy goals, or invest in world-leading technology platforms.

When focused on advanced critical technologies, government investment can shape market conditions, unleash America’s dynamic private sector, and foster a pathway for technologies to scale. But one-off investments will not be enough to win, and finite resources mean the nation cannot invest in everything. Instead, the United States must prepare to make targeted and recurring investments to retain its techno-economic competitiveness through 2030.

2 Perspectives: United States

A Past and Future Industrial Strategy

The U.S. government must learn from what worked in the past and pioneer new forms of partnership with the private sector. This learning process will be crucial: if an industrial strategy is implemented poorly, it can cause government waste. Fortunately, history provides plenty of lessons to draw from about what has worked and what has not.

ONE: Industrial Strategy and the American Tradition

America has used industrial strategy throughout its history, often with great success. In 1791, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton called on Congress to boost U.S. competitiveness in manufacturing industries. Over the next century, his vision was realized as government investment in roads, canals, railroads, and manufacturing positioned the United States to lead the Second Industrial Revolution. During the opening days of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation chartering the Transcontinental Railroad, unifying the Pacific coast with the Eastern seaboard. By 1881, the United States boasted over 100,000 miles of track—about as much as Germany, Great Britain, France and Russia combined.

During the 20th century, industrial strategies built around public-private partnership helped America to win World War II, beat the Soviet Union to the moon, and develop the Internet. After Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt created the War Production Board, a public-private partnership made up of CEOs, university presidents, and government officials. Over the next three years, the group converted auto assembly lines to production facilities for aircraft, tanks, and munitions. During the Cold War, government contracts and research and development funding for defense-related technologies laid the foundations for the Digital Revolution. Government dollars contributed to the development of microelectronics, computers, the Internet and touch-screens.

TWO: The Fall and Rise of American Industrial Strategy

As the Cold War drew to a close, industrial strategy fell out of favor with American policymakers. Market fundamentalism—the belief that any government intervention in the economy was harmful and counterproductive—took hold, with at best mixed results. Over the past 30 years, real wages for most Americans have stagnated, failing to keep pace with productivity growth. U.S. companies outsourced much of their manufacturing, leaving the country vulnerable to supply shocks. The country is falling behind the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in high-tech manufacturing sectors like lithium-ion batteries and commercial drones.

In recent years, however, the push for industrial strategy has gradually regained momentum, with public-private interventions yielding some major successes. Government intervention helped SpaceX become the world’s leader in space technology. Boosted by a 2012 government contract and measures to block PRC access to America’s space industry, the company has powered the United States to a commanding lead. In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services partnered with the Department of Defense to launch Operation Warp Speed, a public-private partnership that developed and produced COVID-19 vaccines in a record-setting 10 months.

2 Perspectives: U.S. Allies and Partners

Lessons & Approaches

Nations around the world are outpacing the United States in setting forth industrial strategies to future-proof their economies for an age of emerging technologies. The European Union has released an industrial strategy to build a digital and green economy, as well as an ‘EU Chips Act’ that aims to capture 20 percent of global chip manufacturing by 2030. Singapore has aggressively courted automated high-tech manufacturers with tax breaks, subsidized worker training, and grants. Australia’s “Modern Manufacturing Strategy” doubles down on the country’s industrial strengths.

As the United States relearns the lost art of industrial strategy, it should draw lessons from other nations’ successes and failures. A closer look at the experiences of the United Kingdom and Taiwan shed light on what works—and what doesn't.

ONE: The United Kingdom’s Checkered History with Industrial Strategy

Like the United States, the U.K. has a long history with industrial strategy. During the first industrial revolution, London leveraged a technology-focused industrial strategy to position itself as the world’s leading power. In recent decades, the record has been more mixed. The U.K.’s recent experience offers a few key lessons for U.S. policymakers:

Source: Fathom Financial Consulting Limited

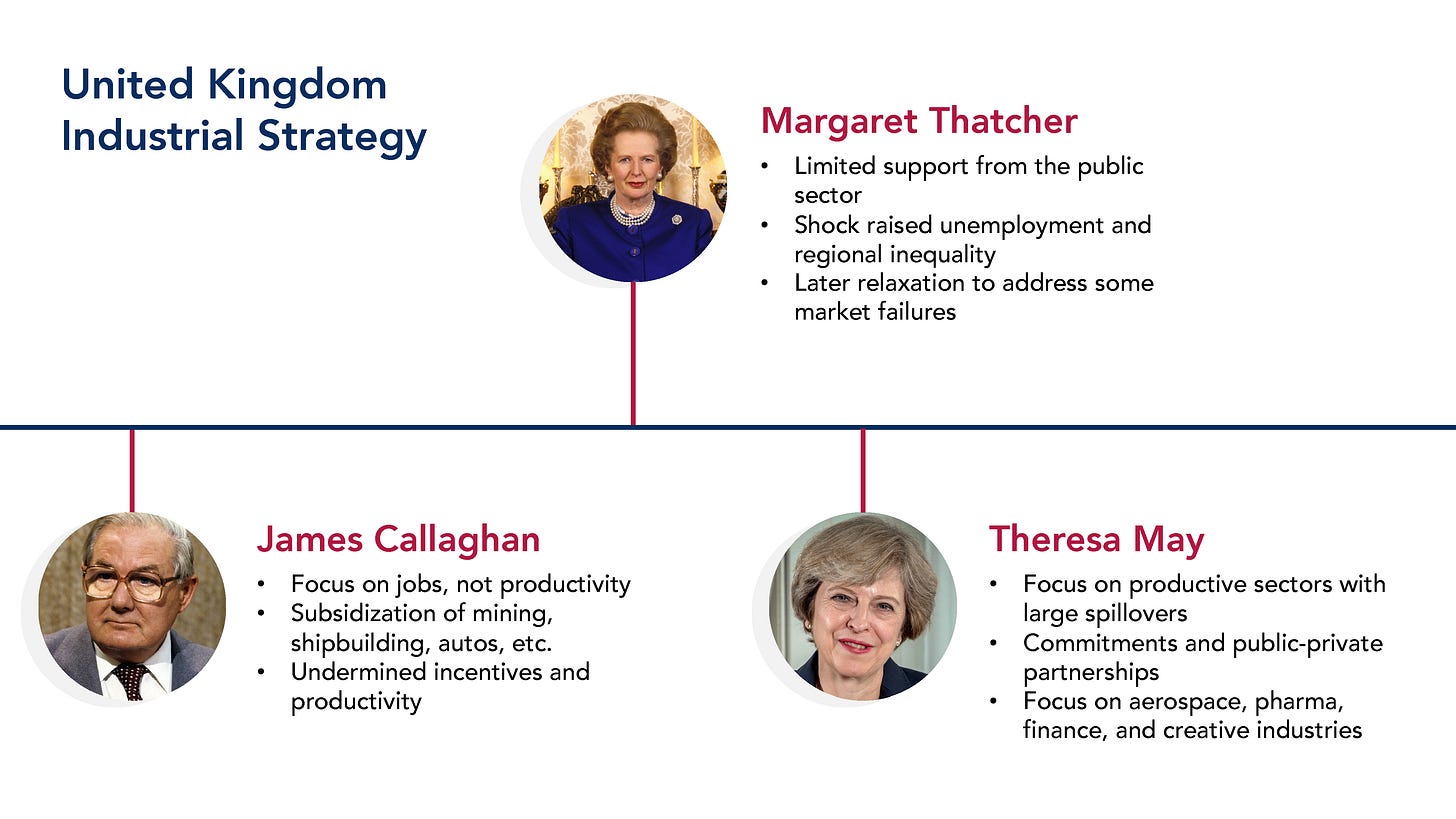

Government should push the technological frontier, not protect legacy industries from competition. During the 1960s and 1970s, Downing Street leaned heavily into industrial strategy—but these policies largely failed. Why? British leaders focused on protecting jobs in established industries—like mining, auto manufacturing and shipbuilding—rather than boosting productivity by placing bets on cutting-edge sectors. Today, the U.K. has lost most of these industries its earlier strategy prioritized (even Rolls-Royce is now owned by Germany’s BMW).

Relying on the free market isn’t enough. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher rolled back these policies during the 1980s, taking a free market approach that banished industrial strategy from the discussion. But this strategy raised unemployment and exacerbated inequality. While markets are crucial to allocating resources efficiently, they are not perfect. Effective industrial strategies monitor where the market falls short—for example, failing to account for productivity spillovers, security concerns, or the social consequences of outsourcing—and offer targeted incentives to address gaps.

Public-private partnerships are key to scaling technology for national advantage. In 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May again reversed U.K. economic policy by releasing an industrial strategy focused on four industries (aerospace, pharmaceuticals, creative industries, and finance). Public-private partnerships were central to this strategy. The May government supported Aerospace Technology Institute, a public-private partnership which fully matches industry R&D funding which has awarded nearly $2 billion in grants.

TWO: Taiwan’s Pro-Competition Industrial Strategy

Taiwan has leveraged industrial strategy to transform itself from one of the poorest countries in the world in the 1950s, to a low-end manufacturing hub in the 1970s, to an advanced technology producer today. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the most prominent example of Taiwan’s successful industrial strategy, is the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturer. Through a combination of incentives and public-private partnerships, Taiwan enabled entrepreneurs in key sectors to access capital and grow their businesses.

Government incentives are key to promoting technology competitiveness. In 1973, Taiwan launched the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), a public laboratory that provided joint research, technical services, and advice to its nascent electronics industry. The Taiwan government also provided incentives and capital to foreign and domestic electronics firms. By blending government support with healthy competition, Taiwan’s strategy spawned TSMC in 1987 and supported its growth when the company struggled to find investors in its early stages. Today, Taiwan’s government remains TSMC’s largest shareholder.

Government can help foster innovation hubs. Following the example of Silicon Valley, Taiwan fostered the development of regional innovation hubs, such as the Hsinchu Science Industrial Park (HSIP) in 1980. Companies in HSIP – located near leading universities – enjoy special tax breaks and other incentives. TSMC is headquartered in HSIP, which is home to an additional 500 companies.

Industrial economies depend on people. Taiwan made major investments in higher education and supported the return of high-skilled engineers. In the 1980s, over 180,000 Taiwanese engineers returned from work or university in the United States, bringing their skills and know-how with them. Morris Chang, the founder of TSMC, was educated at Harvard, MIT, and Stanford and worked at leading U.S. microelectronics companies. At the same time, the Taiwan government invested heavily into higher education, building industry-specific training capabilities at local universities.

2 Perspectives: China

The Party’s Long-Term Plan

The PRC’s history with industrial strategy stretches back to the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In 1921, twelve CCP members held the Party’s first National Party Congress (NPC) at a small house in Shanghai. By 1953, one of the members of the founding group—Mao Zedong—had become Chairman of the CCP and issued the country’s first five-year plan (FYP). Last year, Beijing issued its 14th FYP, which maintains continuity with many of the original themes: a strong focus on manufacturing, emphasis on large-scale infrastructure projects, and a call for reducing imports and increasing industrial exports.

Though the core tenants of the CCP’s Marxist-Leninist economic planning have remained consistent, a return to that same house in Shanghai reveals a very different China. The small gray structure has become a museum commemorating the CCP’s first NPC, but it is now surrounded by a luxury shopping district. Nearby, storefronts for popular Western chains, luxury goods, and fine dining have become a staple of this flourishing district – a reflection of the PRC’s economic miracle and long history of state-led economic development mixed with growing consumerism. Supply chain shocks that reverberated globally from Shanghai’s COVID lockdowns this spring were a reminder that the Party will put social control ahead of economic dynamism when it has to choose.

ONE: Key Takeaways from China’s Industrial Strategy

The PRC’s rise as a techno-economic power raises questions as to whether market-oriented democracies or a single party Marxist-Leninist dictatorship can better organize for industrial strategy. American pundits rightly warn against trying to “out-China China,” but the conversation often stops there. Closer scrutiny is required. China’s industrial policies have led to duplication, waste, and high corporate and local government debt. But several features of the CCP’s approach should make the United States take notice:

Strong emphasis on planning. China’s industrial planners are busy and putting their money where their mouth is. In 2019 alone, Beijing spent an estimated $248 billion on its industrial policies. Beyond China’s 14th FYP, which outlines the country’s broad industrial agenda and priorities for techno-economic development, China also has Made in China 2025, which aims to increase global market share in key sectors, and a National Informatization Plan, which establishes an agenda for national technological modernization, among others. “Letting the free market take care of it” is an insufficient American rejoinder. The United States needs an industrial strategy focused on technology to ensure it can compete. As President Eisenhower pointed out, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

A strategic approach to data. The CCP has rewritten economic theory by including ‘data’ as a distinct factor of production, illustrating how, in its view, data is not just a byproduct of technology, but the lifeblood of the digital economy. Since then, Beijing has endeavored to build out both its data governance framework and the digital infrastructure to support it, with plans to spend some $2.7 trillion over the next five years on telecom networks, data centers, and satellites.

The challenge for the United States and its allies is not about economics alone. Competition will determine who writes the rules for how electronic data are configured, shared, managed, and accessed. The CCP’s ruthless use of data to control its population – like its mass surveillance program in Xinjiang – paints a dystopian picture of what the future could look like if the Party achieves its ambitions for total state control over data. The PRC is also trying to rally international support for its approach to data security and privacy.

To compete, America needs to mobilize on two fronts. Domestically, the United States needs a coherent national strategy for leveraging data as an asset, making data resources and insights available to innovators while protecting privacy and security. Internationally, forging an allied approach to data governance fostering open, secure data flows will not be easy, but doing so could offset the CCP’s plan for digital dominance.

Encouraging sub-national experimentation. Despite the CCP’s highly-centralized planning processes, it has left room for experimentation at the local level since the 1980s. Taking their cue from Beijing’s national-level plans, China’s provinces are competing to become the country’s leading innovation hubs in sectors ranging from autonomous vehicles to data exchanges. In a similar vein, for the United States, innovation does not happen at the national level alone. America needs to harness the dynamism of its 50 states and territories to foster new innovation ecosystems and technological breakthroughs.

TWO: China’s (Five-Year) Road Ahead

At the PRC’s 20th National People’s Congress this fall, the Party will grade itself on its techno-economic development over the past five years and chart the course for the country for the next five years. Most signs point to China’s President Xi Jinping securing a third term, which may embolden him to assert an even stronger hand over the economy and raise new questions on whether autocracy and innovation can coexist in the long term. Regardless, what is assured is the PRC’s continued focus on building a strong industrial manufacturing base and reducing its dependencies on exports – a nod to the original FYP aims established in 1953. What is less certain is whether the CCP’s approach is sustainable over the long term amid China’s dimming economic prospects. A demographic time bomb, high debt, and sharply slowing growth in the wake of zero COVID policies are just a few of the problems casting shadows on the CCP’s way forward.

Conclusion: The Way Forward

Globally, high inflation and perhaps a looming recession raise the prospect of economic turbulence, underscoring the importance of domestic resilience to ensure the economy can bounce back quickly following periods of economic hardship. Economists and policymakers have long used public investment as a counter-cyclical tool to spur economic activity during slowdowns and lay a resilient foundation for future growth. In an era where technology competitiveness forms a key pillar of national power, federal incentives—especially tax incentives—will be even more crucial to support startups and manufacturers in strategic industries.

Congress can take immediate, needed action to bolster domestic manufacturing and invest in the American workforce. To do so, the government has a variety of tools at its disposal: tax breaks, purchase agreements and other incentives can de-risk private sector investment in strategic industries, like semiconductors and critical minerals. Governments at all levels should double-down on training programs to address immediate workforce gaps, offering new career opportunities to workers at any skill level. Greater investment in the American workforce may also yield solutions to the U.S. economy’s slowing productivity growth.

All of these steps will require sustained partnerships with the private sector, academia, and labor groups. Some may risk short-term financial losses and challenge the deep-seated free market orthodoxy that has long dominated U.S. economic policymaking. Yet as a part of forward-looking industrial strategy, they can help America weather near-term economic turmoil and become more secure and prosperous for decades to come.

Contributions: This newsletter includes contributions from Fathom Financial Consulting Limited.

Photo Credits: Alexander Hamilton; Franklin D. Roosevelt; Dwight D. Eisenhower; James Callaghan; Margaret Thatcher; Theresa May; Morris Chang; Li Kwoh Ting; Site of the CCP’s first National People’s Congress; Starbucks, Shanghai; Mao Zedong; Deng Xiaoping; Xi Jinping.