How Can the Intelligence Community Remain Indispensable to U.S. Policy Makers?

A survey of policy makers by the Special Competitive Studies Project Offers Some Critical Insights.

Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this edition of 2-2-2, SCSP’s Intel Panel Members offer critical insight in a survey of policy makers. This newsletter edition was originally published as a guest piece in the April 25, 2023 edition of Cipher Brief. It has been republished in SCPS's newsletter with their permission.

In an era of information overload, the rise of AI and machine learning tools, and intensifying competition with China, one question looms large: Is the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) effectively supporting U.S. policymakers? To explore this question, we at the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP) carried out an extensive e-survey from 1-25 March 2023. We reached out to 299 current and former national security officials to evaluate the intelligence support they received from the U.S. Intelligence Community during their time in the government.

A total of 86 people took our survey. Of those who took the survey, 27.9% are still serving in the government, 22.1% served as recently as the last year, 25.6% in the last three years, and 20.9% in the last five years. Those who took the survey included senior leaders (41.9%), managers (20.9%), advisors (25.6%), and analysts (5.8%). The respondents included, among others, a National Security Advisor, two Deputy National Security Advisors, general and flag officers from the various military services, including those who had commanded in combat or held leadership positions in the European and Indo-Pacific theaters, foreign service officers, civil servants, and political appointees.

Respondents had experience working in the executive (72.1%), legislative (7%), and judicial (1.2%) branches of the U.S. government, as well as in the military services (18.6%) and independent agencies (1.2%). The respondents worked on defense policy (26%), diplomacy (19%), intelligence matters (16%), commerce (13%), trade (11%), sanctions (8%), and development (6%).

KEY FINDINGS

Our survey finds that intelligence remains indispensable to U.S. policymakers. However, the intelligence community faces a serious risk of losing its indispensable role of providing information advantage for decision advantage to U.S. policymakers.

The demand for, consumption of, and satisfaction with intelligence remains exceptionally high among U.S. policymakers. Nearly three quarters of respondents reported consuming intelligence on a daily basis and spending 30 minutes or more per day consuming intelligence. Importantly, policymakers reported that intelligence influenced their decisions considerably and generally improved policy outcomes.

At the same time, nearly a quarter of policymakers surveyed indicated that they wished to have received better intelligence to inform policy outcomes. Nearly half of respondents indicated that intelligence only occasionally impacted their days, with another 15% noting that it rarely impacted their day as policymakers.

Most importantly, the survey reveals that U.S. policymakers are seeking more rapid, accessible, digestible, and directly relevant intelligence insights.

U.S. policymakers appear to rely primarily on open sources for most of their daily information needs and breaking news. The majority of policymakers said that they relied on open sources for their daily information needs, and two thirds said they get breaking news information from open sources.

U.S. policymakers appear eager to use AI tools, such as ChatGPT, to generate intelligence insights, viewing such insights as similarly good or even superior to human insights, despite some suspicion about the performance of such tools.

U.S. policymakers appear to want better support from the Intelligence Community on (a) economic and (b) science and technology matters, in addition to the quality support reported to receive on politics, military, and strategic decision making.

And, U.S. policymakers increasingly favor the use of visualizations and digital formats, in lieu of written reports and briefings to receive data and analysis.

These findings are generally consistent with the research we at SCSP have been conducting over the past year. They point to two important conclusions. First, intelligence will be essential to the ability of U.S. policymakers to achieve decision advantage in the technology-charged competition with China. And, second, the U.S. Intelligence Community must radically adapt in order to rise to the occasion. It must provide open source intelligence, adopt new technologies, especially AI, bring forward broader insights, particularly on S&T and economics, and design easier-to-digest products. Absent these changes, the risk of irrelevance for the U.S. intelligence community is real.

DETAILED FINDINGS

Finding 1: The demand for, consumption of, and satisfaction with intelligence remains exceptionally high among U.S. policymakers.

Policymakers have a high demand for intelligence, with over 73% of surveyed individuals consuming it daily. Moreover, over 74% of respondents spent 30 minutes or more per day on intelligence consumption, and nearly 28% allocated an hour or more to it.

Policymakers reported that intelligence played a fundamental role in their work, by influencing their decisions considerably and by generally improving policy outcomes. Over 57% of respondents indicated that intelligence influenced their policy decisions either frequently (43.9%) or every time (13.4%). And nearly half of respondents (48.8%) thought that intelligence improved policy outcomes either frequently (35.37%) or every time (13.41%). Intelligence, however, had less sway over day-to-day decisions, with over 46% of respondents indicating that intelligence occasionally impacted their daily decisions; and over 35% indicating that intelligence impacted their daily decisions frequently (23.17%) or every time (12.2%).

The Intelligence Community is perceived as being very timely in addressing policymakers’ demands, although their responsiveness appears to be much faster for taskings compared to requests. Over 65% of the respondents noted that the Intelligence Community responded to their requests or taskings either on time or faster than the specified deadline. However, for requests, only 4.7% of respondents noted to have received a response from the IC faster than the specific deadline (60.5% still noted that they had a response to their request within the specified deadline). For taskers, however, 50% of respondents noted that they received their response faster than the specified deadline (and another 15.1% noted that they got their response on time).

Finding 2: Policymakers express a clear demand for improved IC performance.

Policymakers see significant room for improvement in support by the Intelligence Community. They rely on and acknowledge its value, but express a desire for additional support. Approximately 72.9% of respondents desired improved intelligence for policy decisions, with 28.2% wanting it every time and 44.7% frequently.

Policymakers turn to the Intelligence Community principally to understand the current state of play (27.8%) or to anticipate future developments (26.2%), but somewhat less for specific decision support (21%) or to query facts (18.3%).

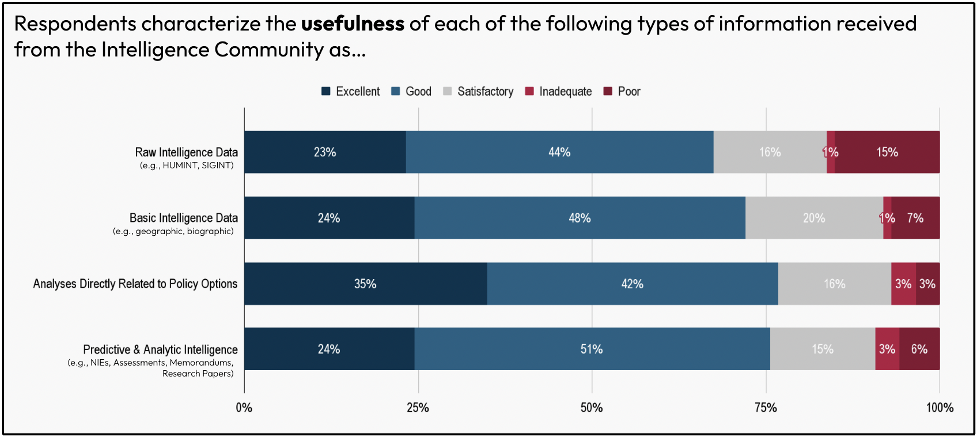

The two areas for potential improvement included analysis directly related to policy options and predictive intelligence. Both of these categories showed room for improvement when it comes to the quantity, quality, and usefulness of intelligence that policymakers received.

Finding 3: U.S. policymakers primarily rely on open sources for most of their daily information needs and breaking news.

For daily information needs and breaking news, policymakers predominantly use open sources. For daily information consumption, over half (52.5%) relied on news media (29%), social media (18.4%), or academic publications (5.1%). In the survey, they leaned more on news and media (29%) than the Intelligence Community (23.2%) or government sources (22.1%). For breaking news, two thirds (66.2%) of respondents sourced information from open sources, primarily news and media (43.4%).

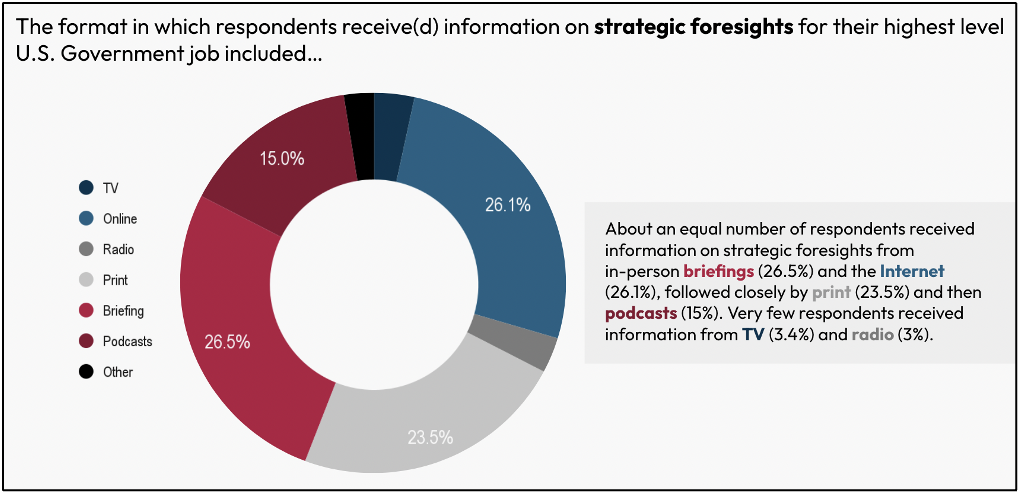

For strategic foresights, however, a majority of respondents sourced, in aggregate, information from controlled sources (49.9%), with 26.3% of respondents turning to the Intelligence Community and another 23.6% to other government sources. Surprisingly, nearly a quarter of respondents also turned to academic and scientific publications for information on strategic foresights.

Finding 4: U.S. policymakers appear open and even eager to use AI tools, such as ChatGPT, to generate intelligence insights, viewing such insights as similarly good or even superior to human insights, despite some suspicion about the performance of such tools.

The survey indicates that a vast majority of national security professionals would be eager to use AI tools, such as ChatGPT, to generate intelligence insights, with a majority also indicating that they would view such insights are either on par with or superior to those generated by humans. Over three quarters of all respondents (76.8%) said that they would be very or somewhat likely to use insights derived from AI tools with access to classified intelligence. The majority of respondents (55.8%) indicated that they would view AI-generated intelligence insights as similar (44.2%) or superior (11.6%) to insights derived by human analysts.

Despite the strong desire to use AI tools for intelligence insights, a significant portion of the respondents still had reservations about the quality of the analytic output from AI tools and were somewhat split on whether they could fully trust such insights. Over 44% of respondents indicated that they would view AI-generated insights as inferior to those generated by humans. On the issue of whether to trust the AI generated insights, 37.2% of respondents were neutral, while 36% of respondents were either somewhat likely (26.7%) or very likely (9.3%) to trust AI-generated insights. These conflicted views on the quality of AI generated intelligence insights and whether to trust them may well be a reflection of the fact that tools such as ChatGPT do not yet exist in the classified world. Therefore, their introduction could shift the attitudes of policymakers – for better or worse. At a minimum, it seems to indicate that policymakers would strongly expect to see some level of human-machine teaming in the early days of introduction of AI tools for intelligence insight generation.

Finding 5: U.S. policymakers appear to want better support from the Intelligence Community on (a) economic and (b) science and technology matters, in addition to the quality support they receive on politics, military, and strategic decision making.

When asked about topics that the IC does best and topics that it could do better, the respondents appeared most clearly satisfied with intelligence support on topics such as politics and military matters.

The two areas that the respondents desired most improvement were economic matters and science and technology. Only 3% of respondents felt that economic matters were the best area of intelligence support; and 26% identified it as an area in clear need of improvement. Only 10% of respondents felt that science and technology were the best area of intelligence support; and 29% identified it as an area in clear need of improvement. On one topic – strategic decision making — there was a paradox among respondents. While 27% of respondents felt it was a topic on which the IC excels, 28% of respondents also identified it as a topic on which the IC could improve the most.

Finding 6: U.S. policymakers appear to be developing a preference for visualization of data and analysis, and digital format in general, in lieu of written reports and briefings.

With respect to the format of intelligence products, the IC continues to push its products primarily in written format or via briefings. However, the policymakers appear to be developing a stronger preference for data and visualization and emailed products.

Respondents indicated that of the totality of intelligence information they received, nearly 60% was received in writing or via briefings.

When asked how they wished they had received their intelligence products, written products and briefings constituted only 47.7% of the format. The preference for email submissions increased from 11.6% to 14%, and the preference for visualization increased from 3.5% to 11.6%.

For their daily information needs, the surveyed policymakers received their information primarily from new digital sources - 25.8% online, and another 9.9% via podcasts. In-person briefings were also an important source of information (22.6%). Print remains a source (19.8%), while TV accounted for 14.5%. A majority of respondents received information on breaking news from the Internet (32.8%) and TV (22.4%). In-person briefings (15.9%) served a limited role as a source for breaking news.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Among those surveyed, three intelligence entities were the primary providers of intelligence – CIA (32.6%), DIA (25.6%), and INR (12.8%), respectively. When asked who they would have preferred to have been their intelligence provider, all three entities experienced a considerable decline. On the other hand, respondents’ preferences for entities such as NSA, DNI, and military intelligence organizations grew significantly.

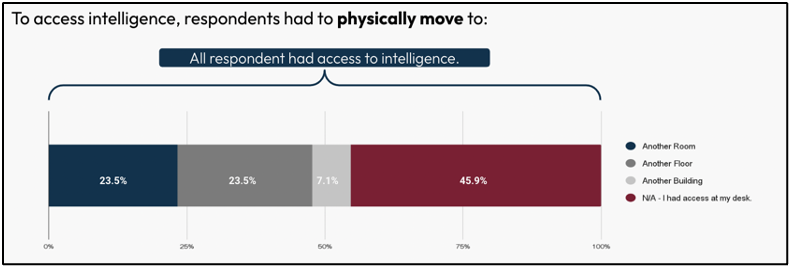

Physical access to intelligence remains an issue. The majority of respondents (54.1%) had to leave their desks for another room, floor, or building altogether to access intelligence. Less than half of the respondents (45.9%) did not have to leave their desk to access intelligence. These numbers were surprising, since nearly 42% of the respondents reported having worked as senior leaders and another 21% as managers in the government. Nearly a quarter of respondents had to go to another room to access intelligence, and another quarter had to go to another floor, with over 7% having to go to another building to access intelligence.

LIMITATIONS

It is important to note potential biases in these results, including nonresponse bias, as not all invited participants completed the survey. This may lead to an over- or underrepresentation of certain perspectives or experiences. Moreover, participants who are no longer serving in the government may be subject to hindsight bias, potentially influencing their recollection of events and experiences.

The survey was exclusively administered via Google Forms, limiting participation to those with access to Google services and compatible email platforms. Consequently, not all individuals, particularly those working in controlled environments, could access and complete the survey. This restriction may have impacted the overall representativeness of the survey results.

The sample for this analysis is restricted to policymakers with whom SCSP staff have either engaged or interacted with previously.