Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP). In this edition of 2-2-2, SCSP’s Channing Lee, Associate Director for Foreign Policy, shares visualizations of the U.S.-PRC Tech Competition.

Join us on May 7-8, 2024, for the AI Expo for National Competitiveness, the first of its kind in Washington, D.C., in coordination with the second Ash Carter Exchange on Innovation and National Security.

For more information on how to exhibit, sponsor, or attend visit our website.

Mapping the U.S.-PRC Tech Competition Landscape

From social media (TikTok) to online shopping (Alibaba) to mobile phones (Huawei) and everything in between, companies from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are now ranked among the world’s most valuable tech firms, alongside U.S. household names.

As policymakers scramble to confront the challenges of the tech competition, it is helpful to consider where and to what extent PRC tech is ubiquitous, and how the presence of PRC tech compares to that of U.S. tech.

In SCSP’s first report, Mid-Decade Challenges for National Competitiveness, we created the map below to illustrate the ubiquity of PRC telecommunications presence around the world. The map captured the scope and scale of the challenge the United States faces in the race for 5G, illustrating just how widely PRC telecommunications equipment – as well as other activities of Huawei and ZTE – have spread around the globe, and demonstrating how much success the two companies have achieved in recent years.

The 5G story has become the classic example of how PRC tech rose to dominate the global market. The U.S. Government has since added Huawei to the U.S. Entity List, and other countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan have issued various levels of bans on Huawei networks and equipment. The key lesson learned here is the criticality of safe, reliable, and secure network infrastructure to support the data flows that power digital platforms and other emerging technologies. To ensure the United States does not get “5G’d” again, SCSP’s National Action Plan for U.S. Leadership in Advanced Networks provides a strategy for how the United States and allies and partners can reassert leadership in 6G and future generations of connectivity.

But what about other technologies? Advanced surveillance equipment, e-commerce, digital payments systems, social media, ridesharing, and mobile phone sales are other sectors worthy of analysis.

Advanced Surveillance Equipment

PRC companies are dominating in the market for advanced surveillance equipment. Hikvision and Dahua are not only China’s top manufacturers of surveillance technology, but also the two largest video surveillance companies in the world by revenue.

There is no comparable U.S. or partner alternative to PRC surveillance equipment, which leverages artificial intelligence and has made the PRC the global leader in facial recognition technology. This can primarily be attributed to privacy concerns; mass, centralized video surveillance of people is simply not something democracies do. However, for countries seeking such surveillance capabilities, PRC technology — and the comprehensive training and infrastructure package that accompanies it — is an enticing option.

E-Commerce

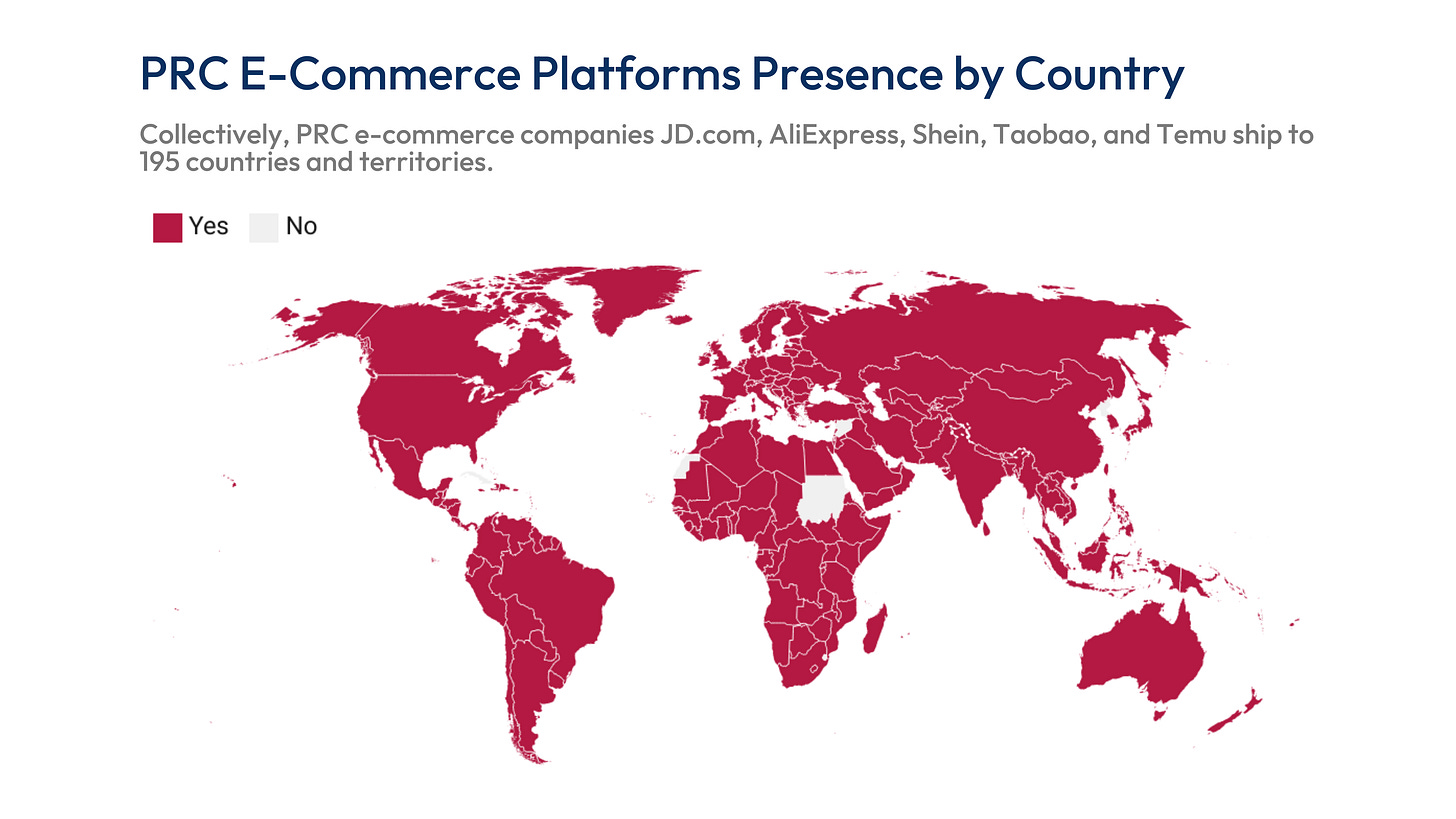

JD.com, AliExpress, Temu, Taobao, and Shein are just a few of the PRC’s leading, international e-commerce companies, together generating billions of dollars each year in revenue. Alibaba, which owns AliExpress, and Pingduoduo, which owns Temu, come second and third respectively behind Amazon among the world’s largest e-commerce companies by market cap.

PRC companies ship everywhere Amazon does, but PRC companies also ship to 78 additional countries to which Amazon does not; many of these countries are in Africa. Some of these companies, such as fast-fashion retailer Shein and Amazon-like behemoth Temu, have also come under scrutiny for allegations of forced labor practices. Interestingly, Amazon is also a popular platform for Chinese companies to sell their products.

Digital Payments

PRC-based companies have built sophisticated digital payments systems that leapfrogs the credit card system. Alipay was incorporated in 2004 by Alibaba, six years before the launch of AliExpress. WeChat Pay, owned by parent company Tencent and referred to as Weixin Pay in China, was launched more than a decade later in 2013. The two companies now facilitate the majority of payments in China, even those in rural areas, and are currently available in 135 countries.

While there are differences in how PRC and U.S. digital payments systems work, we can map the global availability of Alipay and WeChat Pay against that of PayPal, Apple Pay, and Google Wallet (Venmo, owned by PayPal, is only available in the United States) – PRC platforms are available in 24 additional countries where U.S. platforms are not. However, the digital payments sector is unique: though expansive, PRC apps are designed for use by PRC bank account holders (these companies initially expanded their presence overseas to facilitate payments for Chinese tourists traveling abroad and only began accommodating foreign tourists in 2019). Therefore, the ubiquity of Alipay and WeChat Pay does not necessarily mean the United States is “losing” in payments systems, especially when the U.S. financial system and dollar transactions remain central to global financial flows. Though the two companies announced in July that they would begin accepting foreign credit cards, adoption from non-PRC citizens has been limited.

Social Media

Video-sharing app TikTok broke records for reaching 100 million monthly active users in only 9 months back in 2015. It now boasts more than 1.5 billion monthly active users and is expected to reach 2 billion by the end of 2024. While Douyin, TikTok’s sister app that operates in the PRC, has 743 million monthly users, the United States has the world’s most TikTok users at 117 million. If we look at user penetration (ratio of TikTok users to population), the United Arab Emirates leads with 86% penetration; U.S. TikTok penetration remains lower, at 34%, while Douyin penetration in the PRC is 52%. More than 70% of adult users are between the ages of 18 and 34. TikTok is also the most downloaded app in the United States, occupying the #1 spot in the App Store since 2021. TikTok’s AI-enabled algorithm learns users’ preferences and curates content for users independently from other users’ preferences. As a result, the PRC-developed TikTok algorithm has become addictive, notwithstanding the potential for PRC-based actors to influence content that appears on users’ feeds around the world. The PRC’s National Intelligence Law, which privies government access to all PRC companies’ data for national security reasons, makes TikTok all the more dangerous should the occasion arise for Beijing to request access to global TikTok user data, even if the company is now headquartered in Los Angeles and Singapore.

While the platform differs from TikTok in how it facilitates user interactions, we selected U.S. company Instagram, owned by Meta (formerly Facebook), to compare the presence of their users worldwide. Despite TikTok’s rapid growth, Instagram remains more prevalent globally. Still, presence is an imperfect measure here, as user engagement and time spent on platforms (both proprietary business data that is not easily accessible) are key metrics, and anecdotal information points to Tiktok’s addictive strength in this regard.

Ridesharing

Didi, which began as a rideshare company in 2012 but has since expanded its operations to include the gamut of food delivery and financial services, is the PRC’s leading ridesharing service. Sometimes referred to as China’s Uber, the Beijing-headquartered company has now expanded to 14 countries outside of the PRC.

Uber currently far outpaces Didi internationally. Since Didi bought Uber’s operations in China, it is the only country in which Didi operates and Uber does not. In addition to the 14 countries where both companies operate, though, Uber has business in 55 more countries worldwide, making it the dominating rideshare company worldwide.

Mobile Phone Sales

Finally, we examine mobile phone sales. PRC phone brands Xiaomi, Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, and the like have gained in market share over the years. These phones are especially popular in middle-income and developing countries, where consumers can buy smartphones at lower costs. PRC-based mobile phone companies occupy the greatest market share of India.

We can compare the market share of PRC phone companies to that of the United States’ Apple, Google, and T-Mobile. PRC phone companies lead in 114 countries, while U.S. companies lead in only 84.

But the global mobile phone market cannot solely be analyzed in a U.S.-PRC vacuum: allies and partners are also very competitive in this space. Thus, if we include sales from South Korea’s Samsung and LG, Finland’s Nokia, France’s Alcatel, Japan’s Sony, and the UK’s Vodafone, PRC companies are no longer as competitive. In fact, companies from these “DemTech” countries lead in 162 countries, dwarfing the PRC’s 36 countries.

Lessons Learned

PRC tech platforms presence is only one of many metrics to assess PRC global influence, and the technologies that we selected only scratch the surface of the range of technologies powering the world today. But the lesson here is twofold. First, the United States remains competitive in some key technology platforms, maintaining the lead in sectors such as social media and ridesharing. Second, in sectors where U.S. companies are not leading, like mobile phone sales, allies and partners are capable of levying their strengths to ensure that DemTech countries still dominate the global tech landscape. As we compete with the PRC on dominating the most important technologies, we cannot compete alone. Alongside our allies and partners, we can win.

Special thanks to former SCSP Research Assistants Pranav Pattatathunaduvil, Samantha Hasani, and Research Assistant Noah Stein for their contributions to this research.