The Future of Insights: Intelligence in An Age of Data-Driven Competition

SCSP’s Intelligence Interim Panel Report

Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this edition of our newsletter, we summarize our second interim panel report. It’s focused on the intelligence in an information-rich and geopolitically competitive war, and how the United States Intelligence Community can best position itself to unlock new insights in support of U.S. statecraft.

In this edition of 2-2-2, Director for Intelligence Peter Mattis and Associate Directors for Intelligence Meaghan Waff and Katherine Kurata summarize SCSP’s second interim panel report.

SCSP Intelligence Panel Releases Interim Panel Report

Last week, the Intelligence Panel released its Interim Panel Report “Intelligence in an Age of Data-Driven Competition.” It expands on the intelligence chapter in Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness and is the second of six interim reports from the overall work that SCSP has conducted over the past year.

You can view the reports by clicking the report titles above or by visiting our website.

Reach out to info@scsp.ai with any questions!

INTELLIGENCE IN AN AGE OF DATA-DRIVEN COMPETITION: Highlights from the Intelligence Panel IPR

For the first time since the Cold War, the United States faces a rival – the People’s Republic of China (PRC) – that is competing globally across the economic, political, social, and military domains to reshape, if not dominate, the international order. As the new National Security Strategy of the United States puts it, “The PRC is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it.” For the Intelligence Community (IC), this rivalry will govern not only what U.S. leaders ask of it, but also how it must evolve.

The U.S.-PRC rivalry emerged quietly, becoming wide in scope and fierce in intensity without a visceral moment to mark its beginning. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the eerie electronic chirping of Sputnik in 1957, and Al-Qaeda’s terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001 left indelible marks on the American psyche and government. The initial fear turned to sustained determination. These events galvanized both the U.S. Government and American public to do what was necessary to respond. The ways in which Beijing has surprised the United States cannot be captured as vividly in an image. And that catalytic moment may never come.

The motivation for change must come from U.S. leaders inside and outside the IC. They need to see how today’s world awash in data and geopolitical rivalry challenges the IC – such as the need to provide insight into our adversary’ emerging technologies and the organizations that field them – and how to push change forward without another national catastrophe.

The new context, however, requires more dramatic adjustment than just a change in priorities. The context for intelligence has changed. Capabilities once unique to the IC - top secret satellite imagery, signals intelligence - are now in the hands of the private sector. Even in areas where the IC should have an advantage, such as exposing Beijing’s political interference, journalists, academics, and open source researchers have been able to lead the way.

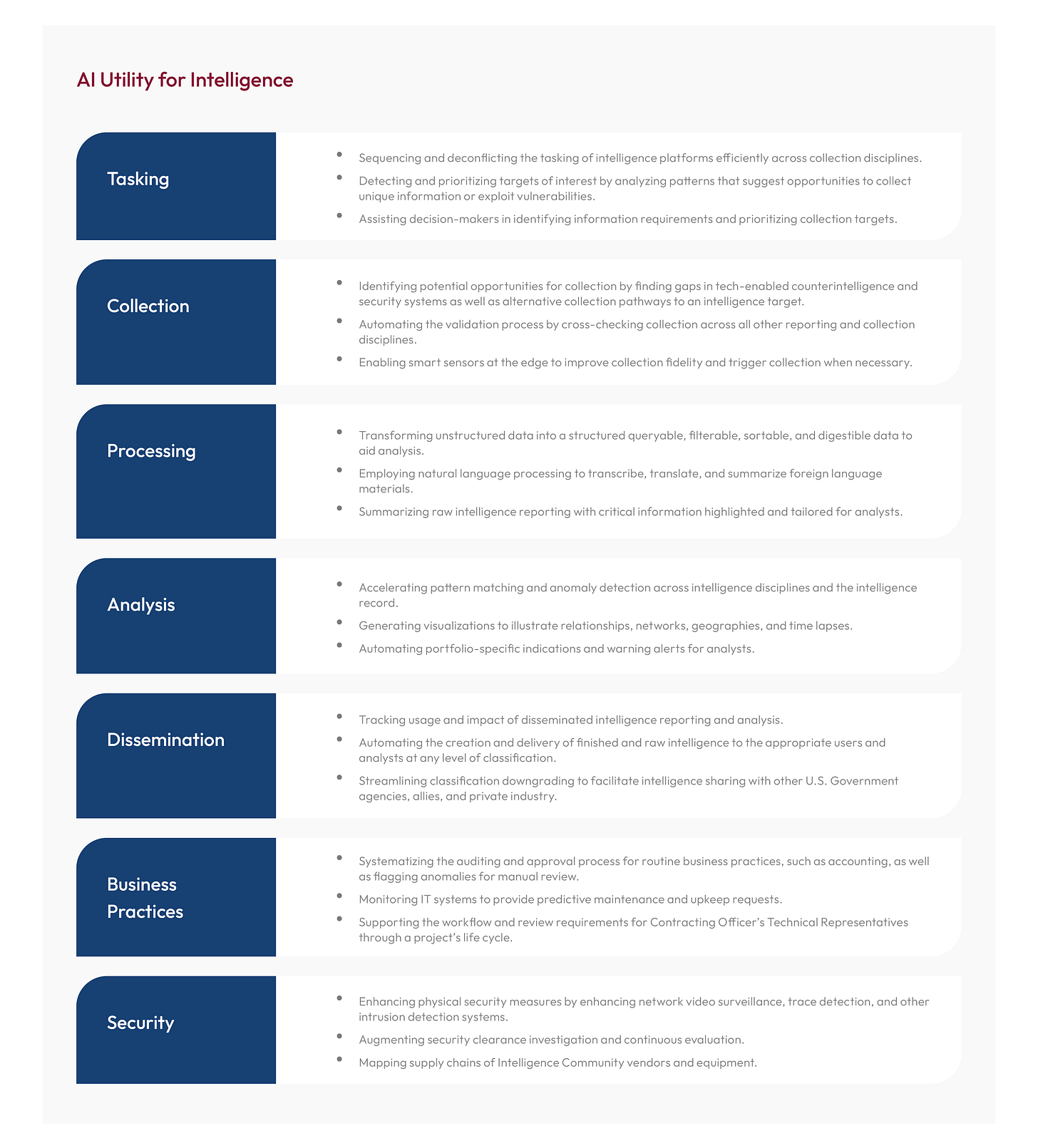

In our interim panel report, we argue that the IC should priorititize the core mid-decade challenge: winning the race for actionable insight. And the IC’s ability to provide competitive advantage to U.S. policymakers will hinge on whether it can integrate and master emerging technologies, particularly AI, and leverage more diverse sources of information from across all domains. More specifically, the IC’s ability to unlock new insights in support of U.S. statecraft will require action in the following areas:

Adapt to the digital era and geopolitical rivalry by modernizing practices to access the best talent, acquire the latest technology, build a community-wide digital infrastructure, and exploit the broadest set of data;

Leverage insights and information from open and commercial sources by creating a dedicated, technology-enabled open source entity to support U.S. decision making;

Create new capacities to capture and master economic, financial, and technological intelligence by establishing a National Techno-Economic Intelligence Center to serve as an economic “nerve center” for U.S. policymakers; and

Counter foreign adversarial influence campaigns through preemptive exposure of their operations, strategic warnings for the U.S. public, alerts for senior U.S. officials who may be targeted by such operations, and adoption of new mitigation technologies.

1. Adapting to the Digital Era

Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines wrote earlier this year that the IC’s difficulties to process its massive collections of classified holdings “reduces the intelligence community’s capacity to effectively support senior policy maker decision-making and further erodes the basic trust that our citizens have in their government.” The IC already has developed some initial answers for how to do this by embracing new digital technologies, including AI. The community’s strategies and implementation plans, however, have been unevenly implemented and insufficiently scaled, despite being among the first in the U.S. Government to experiment with AI.

Today, sustained top-down leadership is needed to drive this transformation, if AI and emerging technologies are to fulfill their potential to transform the IC. In a good signal from the White House, the latest National Security Strategy stated that the IC is adapting to “better address competition” by “embracing new data tools.” Administration officials and Congressional stakeholders will need to ensure that the IC adheres to a coherent vision that aligns strategies, actions, incentives, and metrics.

IC leaders and their designated technology leadership should prioritize projects that build internal tech expertise, improve data standardization and architecture, and support emerging tech adoption at scale across the IC. To do so effectively, IC leaders must first understand AI and emerging technologies – their benefits and limitations – to maximize the opportunities the technology can offer. Education and experience with technology issues for executive and mid-level management will need to be a part of the process.

Secondly, IC managers must find the right combination of people, processes, and technology to enable successful, at-scale digital transformation. It needs people with the right expertise to advance technology; processes to manage areas where humans and technologies converge; and the right technologies to store, process, and move data at immense scale. Integrating these elements is a challenge for any large enterprise, upsetting traditional career paths, workflows, data management, and technology integration. Shifting the IC’s practices will require standardizing and contextualizing data for broader use, building a new digital backbone, and accessing necessary talent. As these elements come together, the IC would gain agility and efficiency in honing on existing applications and applying them to new problems.

The Director of National Intelligence (DNI) should sponsor the creation of a Digital Experimentation and Transformation Unit to run pilot projects that address community-wide challenges on talent, processes, technologies, or acquisition as identified by the DNI and IC agency directors. The unit should be sponsored and empowered by the DNI, with one of the intelligence agencies serving as the executive agent, and with representatives from each member of the intelligence community. The purpose would be to identify and apply the best available technology and expertise in the United States, inside and outside government, to select community-wide problems. The DNI would also need support from Congressional appropriators to ensure the office has the necessary time and support to solve the selected problems. The pilot projects should address a key aspect of the people, processes, technology, and acquisition needs of the IC to accelerate its digital transformation. All projects would need to include programmatic analysis for each participating IC element to ensure successful projects are sustained beyond the new unit. The initial focus areas could include: recruitment of needed expertise, improvement of IT systems interoperability within the IC, automation of cross-collections platforms at the edge for indications and warning capabilities, or creation of an IC-wide knowledge management platform.2. Leveraging Open Source

In an age where most data resides in the open world, the IC risks surprise and intelligence failure without a robust open source intelligence capability. The exponential growth in publicly and commercially available information has outpaced the IC’s capability, or anyone’s for that matter, to fully harness open source in support of U.S. decision making and policy. This has come on top of the decline in the collection, processing, and usage of open source materials through the evolution of IC open source initiatives from the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) to the Open Source Center to the Open Source Enterprise (OSE). Moreover, less attention to collection, user-unfriendly platforms, and overzealous security practices have limited U.S. intelligence analysts’ effective access to and use of government open source resources over time.

While calls for an open source organization are not new, the United States can no longer downplay the value of publicly and commercially available information. The 2022 National Security Strategy took the first step in calling for the IC to adapt organizationally by better integrating open source materials.

The U.S. Government should create a new, well-resourced institutional home for open source collection, acquisition, processing, and analysis. Rather than approaching this entity as an analytic unit, it should be thought of as a collection organization capable of acquiring, processing, exploiting, and disseminating information on a significant scale. All-source analysts cannot do this on their own. This organization also should have the data architecture, computing power, and AI-enabled tools built in from the beginning to be able to handle publicly and commercially available data at scale. The precise organizational model for an open source entity is secondary to ensuring that it addresses the imperative of the open source mission and meets the entire U.S. Government’s needs. For instance, policymakers should ensure that an open source entity have: broad dissemination authorities, expertise, a voice within the IC, public access to its products, a clear mission, and an institutional structure that allows it to act as a gateway for open source information between policy agencies, the IC, and external actors. With these in mind, an entity could be organized in one of four broad ways, each with its own set of barriers and avenues to success.

3. Creating Techno-Economic Intelligence

Economic competition with the PRC, in particular, is wide in scope and fierce in intensity. Consequently, U.S. intelligence must reorganize and retool to defend Americans’ standard-of-living, support a U.S. Techno-Industrial Strategy, and protect the interests of the United States and its allies around the world.

However, before this can even happen, the IC must strengthen its techno-economic intelligence capabilities. It must be able to examine the gears of the PRC’s economy and to have a detailed understanding of the CCP's industrial and technological priorities and pursuits. This includes the PRC's trade behavior, key industries and companies, critical supply chains, and investment flows. U.S. intelligence will also need to understand the PRC’s emerging platforms in technology and finance, especially as these data-collecting, strategic platforms are exported abroad.

The U.S. Government should establish a National Techno-Economic Intelligence Center to capture, master, and disseminate economic, financial, and technological intelligence. This center should coordinate economic threat information and work closely with policymakers on supporting their responses to these threats. Using AI to collect and process economic information at scale, this economic “nerve center” would be able to make economic assessments and forecasts, as well as fuel innovation in economic modeling. Like an economic equivalent of the National Counterterrorism Center, this center, with analysts trained for techno-economic analysis, would warn of foreign threats to the U.S. economy, make sense of rivals’ grand strategies, apprise the U.S. industry about threats such as intellectual property theft and supply chain vulnerabilities, and evaluate opportunities to deploy tools of economic leverage.

To do this, U.S. intelligence also needs the authorities and incentives to make techno-economic net assessments. The deep interconnections between China and the United States through global trade and finance means that it will be essential for U.S. intelligence to have the ability to do complex analysis involving U.S. companies. For this, the Intelligence Community, or select elements within it, needs the authority and internal guidelines to conduct these net assessments while ensuring appropriate privacy safeguards for U.S. citizens.

4. Countering Foreign Adversarial Influence Operations

Foreign disinformation remains an acute national security danger in search of a comprehensive solution. Technological advancements and the emergence of new media platforms have enhanced the speed, reach, volume, and precision of disinformation generated and emplaced by foreign adversaries.

In our interim panel report, we propose a series of actions that could better position the United States to confront the challenge of foreign disinformation operations.

The first action to consider is operationalizing the Foreign Malign Influence Response Center in order to centralize governmental collaboration to counter foreign adversarial influence operations affecting the United States, and allies and partners. The Center would also benefit from technologically-enabled capabilities as detailed in the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence’s (NSCAI) Final Report.

The U.S. Government should also prioritize preemptive countermeasures in three ways. First, the U.S. Government – including the IC – should aim to “prebunk” malign actions through early disclosures of malign actions whenever possible and suitable. Second, it should warn of foreign-backed disinformation through alerts, potentially by partnering with Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to broaden the National Cyber Awareness System to alert the public about foreign disinformation operations of strategic import. Third, the U.S. Government should create a public notice board of adversary-generated false narratives and themes to expose them and encourage public research.

The U.S. Government should also designate and resource an entity to track and counter foreign-directed denigration campaigns against senior U.S. leaders. Our adversaries are working to acquire, analyze, and weaponize data that, empowered by AI, could allow foreign intelligence services to micro-target senior civilian and military leaders by denigrating them in the public domain and orchestrating character assassination efforts.

Finally, the constant evolution of influence operations requires the Intelligence Community – and U.S. Government writ large – to incorporate new technologies and mitigation techniques quickly. To bolster the impact of the suggestions above and existing efforts, the IC should consider leveraging tools like the content provenance standards of the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity to keep pace with, and outrun, digital adversarial influence.

CONCLUSION

U.S. intelligence can deliver on the seemingly impossible and the once-unthinkable. It should be able to rise to the challenges of this new era. The IC, for example, was able to successfully warn the White House, Ukraine, and its allies of the Russian invasion months before its actual occurrence. Early and rapid declassification of U.S. intelligence allowed policymakers to counter Russian disinformation credibly, undermine potential false flag operations, discredit the Kremlin narrative, and strengthen the allied response. Such efforts are possible because the IC and its partners operate the world's largest constellations of human and machine sensors located anywhere from undersea to outer space.

The IC has and can continue to pursue and exploit technology to its fullest potential because of the strengths inherent to American society and its political system. Since its founding, the IC’s ability to access the best talent and technology of the United States has grown. The IC is now more open to talent of any ethnicity and creed than in its past, even if being truly representative of U.S. society is still an ongoing process. The IC also benefits from other asymmetric advantages over its authoritarian counterparts – including its ethos of objectivity, its national mission, and its work with allies and partners.

The recommendations outlined above lay the groundwork for positioning the IC to provide technologically-enabled timely, actionable insights. By focusing on the four broad areas of digital transformation, open source, techno-economic intelligence, and countering foreign adversarial influence operations, the IC will be best positioned to avert intelligence failure in the changing data-rich, competitive environment.