Building a National Delivery System for Data

Taking Stock of China’s 5G, Broadband, and Data Center Buildout

Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this edition of 2-2-2, SCSP Economy Panel’s Senior Director Liza Tobin and Directors David Lin and Warren Wilson take a look at how Beijing thinks about digital infrastructure, its progress on three major tech-driven industrial plans, persistent challenges Beijing has faced during implementation, and key takeaways for the United States.

Introduction

In 2023, producing semiconductors will be central to the Biden Administration’s “modern American industrial strategy.”1 But, as part of a new techno-industrial strategy, policymakers should capitalize on another less-noticed, once-in-a-generation opportunity: upgrading America’s digital infrastructure to unlock the potential of the digital economy. Authorizations for digital infrastructure feature prominently in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and other recent legislation – upwards of $100 billion for broadband, 5G, and other connectivity technologies – representing an important step in Washington’s recognition of the critical role such infrastructure plays in the technology competition.2 Ensuring the funds are used effectively will be essential to fostering American economic growth, innovation, and productivity.

As the United States dives headlong into building out its infrastructure to maximize digital connectivity, it is useful to pause and take stock of how America’s chief rival – the People’s Republic of China (PRC) – is approaching what Beijing has coined “new type infrastructure.”3 Its promises loom large: comprehensive digital infrastructure across China could bolster the country’s position as a global manufacturing powerhouse, bridge the urban-rural divide, and foster broader access to public services in health, finance, and education — but only if the PRC implements its plans effectively.

Digital Infrastructure Policy as Data-Centric Economic Strategy

China’s digital infrastructure buildout must be understood in the context of its broader domestic economic strategy. According to Beijing’s 14th Five Year Plan for the Digital Economy, released in January 2022, the digital economy is made up of “digital technology as the core driving force, data as the key production input, and modern information networks as the primary delivery system.”4 In other words, China’s industrial planners are approaching the country’s digital infrastructure buildout on three levels:

Data is the raw material;

Digital technologies and platforms – mobile applications, algorithms, and things like China’s novel experimentation with data exchanges5 – are vehicles that create value from the data;

Digital infrastructure – wireless networks, broadband, and data centers – comprise the logistics system that transports and delivers the data.

To ensure China has an ample supply of those raw data materials, Beijing is stitching together a comprehensive data governance regime designed to bolster, regulate, and protect its data holdings.6 To create value out of data, in March 2020, PRC authorities issued a directive that elevated data as a “factor of production” alongside land, labor, capital, and technology.7 For digital infrastructure, Beijing has formulated what it hopes to be an integrated strategy to build the world’s largest and most modern “delivery system” for data to boost its digital economy.

Three Pillars of China’s “Delivery System” for Data

As Beijing builds out “new type infrastructure” to deliver and process the raw materials of the emerging digital economy, it has adopted a three-pronged approach. The 5G Set Sail Action Plan focuses on wireless networks, the Dual Gigabit Action Plan targets wired broadband networks, and the Eastern Data Calculated in the West project aims to build out data centers and bolster computing power.

China’s “5G Set Sail Action Plan,” launched in July 2021,8 is Beijing’s plan to deploy ubiquitous wireless 5G networks across the country by setting targets around 5G infrastructure, consumer adoption, and industrial adoption. PRC leaders have framed technology competition in advanced networks around the iterative generations of the technology: “Nothing in 1G,” “lagging behind the rest of the world in 2G,” “breaking through in 3G,” “keeping pace with the rest of the world in 4G,” and finally, “leading the world in 5G.”9 Even though PRC 5G network speeds, on average, are measurably faster than those in the United States,10 China still has work to do before it leads the world in 5G network speeds based on available data.11 That said, Beijing is moving aggressively in at least three areas to accelerate its domestic 5G buildout:

China’s state-owned telecommunications conglomerates are continuing to build 5G base stations across the country at a rapid pace, increasing base station density, and improving network speed and performance.12

Beijing has been rapidly allocating midband wireless spectrum to 5G service providers,13 and began doing so as far back as 2018, a full year before 5G licenses were issued to PRC service providers.14

Finally, China’s emphasis on building standalone 5G networks (SA) rather than non-standalone networks (NSA) built on top of existing 4G infrastructure earlier in the rollout, may have helped with overall network performance since NSA networks are limited in some of the more advanced functionality that SA networks can offer.15

National Average 5G Upload/ Download Speeds by Carrier (2022)16

In conjunction with its nation-wide wireless 5G deployment, Beijing is also pushing a plan for wired fiber optics telecommunications infrastructure through its 2021 “Dual Gigabit Action Plan,” building off a series of fiber-centered infrastructure plans dating back to 2013.17 Although 5G can transmit large amounts of data wirelessly over short distances, it is the physical fiber optic cables that excel at rapidly transmitting data over longer distances, even though the two types of networks are interconnected.18 In China, fixed broadband subscribers are overwhelmingly connected over fiber. In the United States, however, users access broadband through a mixture of fiber and slower DSL, cable, and satellite connections, with cable dominating the market (see chart below). The country’s early transition to fiber — which is more expensive to install than other connections — has allowed China to rapidly take advantage of the higher speeds, scalability, reliability, and security that fiber offers and positions the country well for future network upgrades while fostering a flourishing digital economy.

China’s Network Transition from DSL to Fiber19

U.S. vs. China: Broadband Subscription by Access Medium20

Finally, while the 5G and fixed broadband buildouts are focused on moving data quickly from point to point, Beijing is also trying to address the question of where the data will be stored, processed, and accessed and what energy requirements are needed to accomplish those tasks. Officially launching the “Eastern Data Calculated in the West” (EDCW) project in February 2022,21 China is building a network of data centers across the country. The EDCW project aims to address three key challenges to Beijing’s effort to build a comprehensive transportation system for its data holdings:

The need for enough computing power to compute, process, and convert data into economic value;

The significant energy costs associated with exponential growth in the volume of data processing and storage brought about by 5G and gigabit networks;

And the geographic imbalance of resources in how data is used and supported inside China. Most of the country’s data is generated in its east coast urban centers, but most of the energy resources are located in Western China.

While the project is still in its early stages, PRC planners approved the creation of eight hub nodes and ten associated data center clusters. Government and private investment in the sector is skyrocketing. In the first quarter of 2022 alone, EDCW-related investment reached nearly $30 billion USD.22

Distribution of Data Centers in China (2021) 23

Pitfalls in China’s Approach

China’s digital infrastructure strategy looks great on paper, but the real test is in the execution. Despite being a centrally-planned, state-led economy, there are inescapable political and economic realities that Beijing must address. Three overarching challenges have risen to the surface:

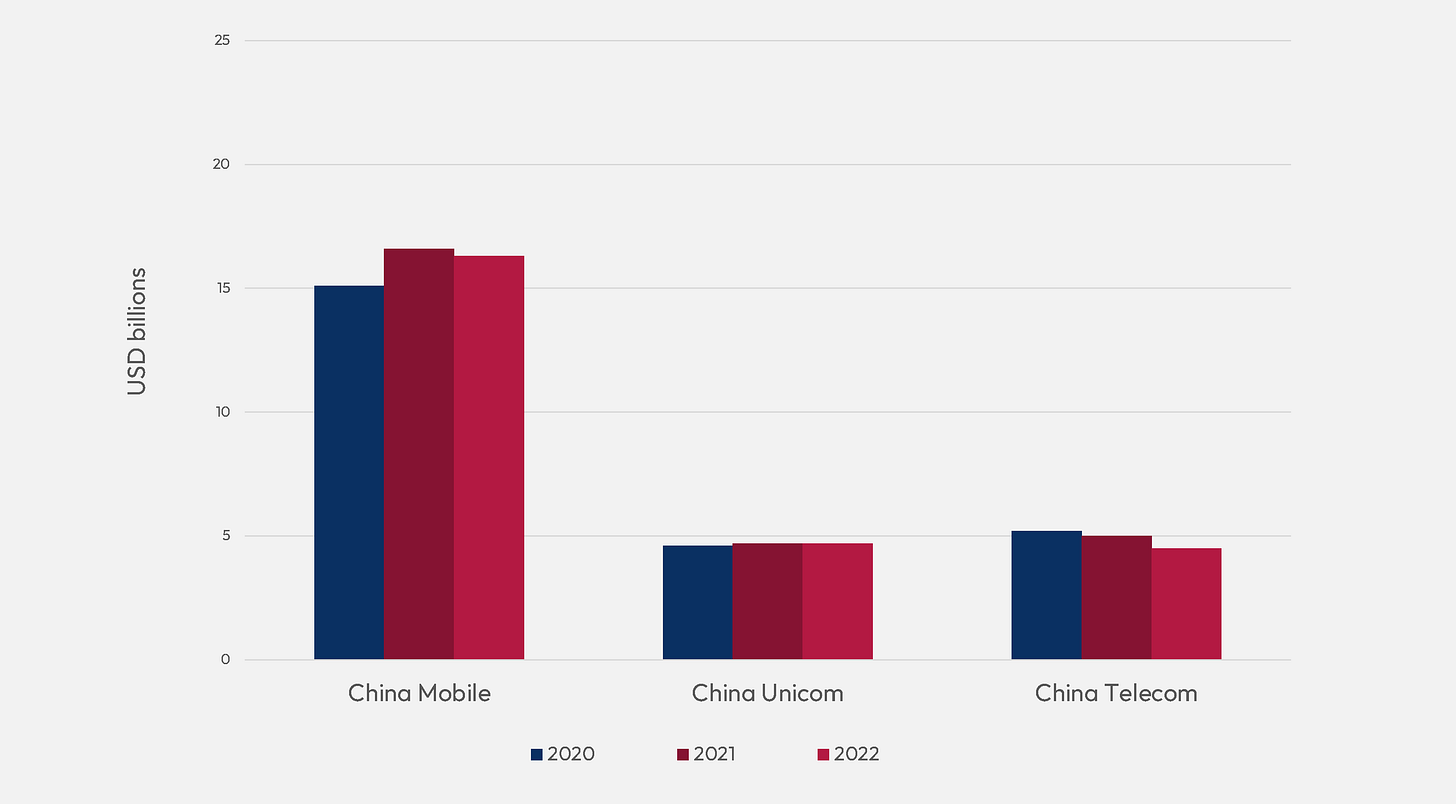

No guaranteed return on investment (ROI). China’s state-directed capital expenditures on 5G, gigabit broadband networks, and data centers are an economic gamble. According to a state-backed PRC think tank, at the end of 2020 – two years into China’s 5G rollout – the country’s telecom providers had still not yet recouped the nearly $120 billion USD they had spent on deploying 4G networks six years prior.24 The ROI scenario for 5G is even more daunting: 5G base stations cost more than twice that of 4G base stations, and may require upwards of 1.5 times the energy costs. In addition, PRC telecom providers face competing priorities to deploy similarly expensive gigabit broadband networks. China’s state-owned telecom providers will likely be operating in the red for some time to come, worsening China’s debt burdens just as the country enters what may be an extended period of stagnating growth.25

Telecom 5G Capital Expenditures in USD billions26

If You Build It, Will They Come? Even though Beijing can claim some first-mover advantage in its rapid buildout of digital infrastructure, businesses have been slow to incorporate 5G into industrial operations, where much of 5G’s economic potential lies, especially for applications like robotics and autonomy. According to one PRC industry media outlet, as of mid-2022, 5G adoption in large-scale industries may be as low as five percent.27 There could be several explanations: 1) PRC firms may see the costs associated with 5G upgrades as outweighing commercial benefits; 2) many original equipment manufacturers may not yet have fully integrated 5G compatibility into their software platforms; and 3) industrial 5G applications have not yet proven their commercial viability. It is worth emphasizing that this problem is not unique to China. In fact, many U.S. and Western press outlets have also openly questioned the practical use-cases of 5G networks, at least for now.28 There is a similar story on the broadband side, with some PRC industry insiders suggesting that there are even fewer proven commercial use-cases for gigabit fiber compared to 5G.29 For EDCW, there is also the risk of overcapacity in computing power, and some industry estimates from 2020 indicate that, on average, data center servers in China were only performing at 50 percent capacity.30

National Ambition Runs into Local Opportunism. As Beijing strives to put a unified front on its industrial plans, the actual execution involves a myriad of national and local stakeholders, whose vested interests may at times run counter to one another. In the case of 5G deployments, the permitting and licensing process for base stations has opened the opportunity for corruption and price distortions. To combat this, local governments have attempted to curb such activities by implementing standard fee structures or other accountability measures.31 In the case of broadband, China’s national tech development plans have run into obstructionism from last-mile monopolies, such as exclusivity deals between telecom providers and real estate developers, which can raise prices for consumers and slow the buildout of network upgrades.32

Takeaways for the United States

There are both obvious strengths and glaring shortcomings to Beijing’s digital infrastructure push. While the jury is still out on whether PRC leaders’ gamble will pay off, it is clear that they have a comprehensive strategy, the strategic patience to let it play out, and a holistic approach to building an interconnected, data-driven national digital economy. A few parting thoughts:

Technology competition will hinge on the degree of integration across the connectivity stack, not on “winning” or “losing” the race to build any one form of infrastructure. The outcome will depend on ensuring the frictionless integration of advanced networks and the data flowing over them – across platforms, regulations, and borders. 5G, broadband, and data centers are mutually-enhancing network technologies and are vastly more powerful when harnessed in tandem rather than in isolation. The United States needs to develop a national digital infrastructure strategy that encompasses wired and wireless network technologies. Furthermore, that strategy needs to be tied to a clear-eyed U.S. approach toward data, and guided by a techno-industrial strategy, to foster economic prosperity, technological innovation, and societal benefits nationwide.

Seeing the full value of digital infrastructure investments will take time, money, and strategic vision. As we argued in our Platforms Interim Panel Report, reaping the benefits of technology diffusion throughout a nation’s broader economy is a long-term project that requires consistent stewardship lest it be lost. Beijing understands this imperative, recognizing that short-term calculations of return on investment should not dictate strategic, long-term investment decisions, and it appears willing to accept the risk that desired outcomes may not materialize. Today, for the first time in generations, the United States has expansive federal funds to dedicate to its digital infrastructure effort.

China’s shortfalls can be converted into U.S. opportunities. As we argued in our Mid-Decade Challenges for National Competitiveness report and again in our Economy Panel Interim Panel Report, even though China is making strides in its 5G infrastructure, core infrastructure alone does not guarantee a competitive edge in the digital economy. As China struggles to convert its early 5G infrastructure successes into broader economic benefits, the competition will be in the development of scalable, enterprise-level 5G applications, an area where U.S. advantages in talent, software, cloud computing, and decentralized innovation offer a leg up.

We should not ignore or underestimate China’s industrial strategies. Rather than dismissing them out of hand, or – worse yet – adopting the fatalistic view that Beijing has already won the race to 5G, Beijing’s moves should be a cue for the United States to get our own house in order. Countries are beginning to move beyond infrastructure build-outs to the enterprise-level uses that these networks will enable. The United States must drive domestic innovation in next-generation industrial applications like advanced manufacturing, smart grids, and other potentially transformative technologies, like autonomous vehicle networks. Smart execution of the significant funds that America has already authorized can bring advanced networks to life, ensuring all Americans benefit from their promise and strengthening the U.S. position in the global technology competition.

This morning our second episode of NatSec Tech was released. Dr. Lynne Parker and Dr. David Danks join host Jeanne Meserve in a conversation on what AI is, how AI is being used in schools, the future of AI governance and more.

Remarks on a Modern American Industrial Strategy by NEC Director Brian Deese, The White House (2022).

Fact Sheet: Department of Commerce’s Use of Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal Funding to Help Close the Digital Divide, U.S. Department of Commerce (2021); Diana Goovaerts, Finding the Money: A U.S. Broadband Funding Guide, Fierce Telecom (2021).

David Dorman, China’s Plan for Digital Dominance, War on the Rocks (2022).

The State Council Notice of the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Digital Economy, People’s Republic of China State Council (2021).

Scott Foster, Shenzhen Data Exchanges Officially Open for Business, Asia Times (2022).

For SCSP’s recommendations on what a National Data Action Plan should look like for the United States, see the Society Panel’s Interim Panel Report, released in December 2022.

Opinions on Building a More Complete Institutional Mechanism for Market-Oriented Allocation of Factors, People’s Republic of China State Council (2020).

5G Set Sail Action Plan (2021-2023), PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (2021). China’s longer term 5G targets appear in national policies such as the 14th Five-Year Plan for Information and Communications Technology Industry Development and the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Informatization, among others.

The Information Office Held a Press Conference on the Development of the Industrial Communication Industry on the 70th Anniversary of the Founding of the People's Republic of China, Government of the People’s Republic of China (2019).

National Mobile Network Quality Test Report - First Quarter 2022, China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (2022); Francesco Rizzato, How the 5G Experience has Improved Across 50 US States and 300 Cities, OpenSignal (2022).

China’s fastest domestic 5G service provider as of early 2022 was China Mobile, which reported download speeds of around 350Mbps, according to the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology. See National Mobile Network Quality Monitoring Report: First Quarter 2022, China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (2022). According to OpenSignal, the world’s fastest 5G service provider is South Korea’s SK Telecom with download speeds of around 470Mbps. For more on global rankings, see Sam Fenwick, 5G Global Mobile Network Experience Awards 2022, OpenSignal (2022).

China Mobile Corporation 2020 Annual Report, China Mobile (2021); China Telecom 2021 Report, China Telecom (2022).

In general, low-band spectrum offers advantages in transmitting over long distances, but often only at data transfer rates slightly better than 4G. High-band spectrum, also known as millimeter wave spectrum, offers high data transfer rates, but can be disrupted by things as small as raindrops and leaves. That leaves mid-band spectrum, which offers the best ratio of distance and data transfer speeds. See Why Mid-Band Spectrum is the 5G Sweet Spot, Forbes (2021).

Graham Allison & Eric Schmidt, China’s 5G Soars Over America’s, Wall Street Journal (2022).

Monica Alleven, “How’s 5G Standalone Doing in the U.S.?” Fierce Wireless (2021).

National Mobile Network Quality Monitoring Report: First Quarter 2022, China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (2022); Francesco Rizzato, USA 5G Experience Report January 2022, Open Signal (2022).

Broadband China Strategy and Implementation Plan, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, (2014).

David Anders, Fiber vs. 5G: Why the Wired Connection Still Reigns, CNET (2022).

Annual Bulletin of Statistics of the Information and Communications Technology Industry, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, (2017); Annual Bulletin of Statistics of the Information and Communications Technology Industry, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, (2022).

FTTH/O = Fiber to the Home/Office; aDSL = Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line. See: Fixed Broadband Deployment Data: December 2019, Federal Communication Commission, (2020); Key Indicators of the Communications Industry During the First Half of 2022, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (2022).

Eastern Data Calculated in the West’ Making Digital Steps Faster and More Stable, PRC Government (2022).

Progress of the East Data and West Calculation (Issue 29), PRC National Development and Reform Commission (2022).

Zijing Fu, Understanding China's’ Eastern Data Western Calculation’ Project, PingWest (2022).

5G Development 2021 Outlook, China Center for Information Industry Development (2020).

5G Development 2021 Outlook, China Center for Information Industry Development (2020).

China Mobile Limited Annual Report 2020, China Mobile (2021); China Mobile Limited Annual Report 2021,China Mobile (2022); China Telecom Corporation Limited Annual Report 2021,China Telecom (2022); China Telecom Corporation Limited Form 20-F, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (2021); The 2020 Annual Reports of the Three Major Operators Are Released, and Investment in 5G Construction Will Continue to Increase in the Future, Cena.com.cn (2021); China Unicom Added 80,000 New 5G Base Stations in the First Half of the Year, Maintaining the Same Annual Expenditure of 35 billion, C114 (2021); 5G Investment Has Achieved Initial Results, and the Three Major Operators Have Deployed Computing Power Networks, Xinhuanet (2021).

Three Questions in Three Years of Licensing: ‘5G + Industrial Internet’ and How Much, Sina Finance (2022).

Scott Moritz & Rob Golum, 5G Has Been a $100 Billion Whiff So Far, Bloomberg (2022); Mark Cameron, Telcos Aren’t Ready to Capitalize on the Value of 5G — Yet, Forbes (2022); The Manufacturing Industry’s Rocky Road to Private 5G, Light Reading (2022).

“Gigabit optical networks are as important as 5G networks, and industrial capabilities need to be comprehensively improved.”, Xinhua (2021).

Empty Data Centres Mushroom in China’s Far-Flung Provinces, Reuters (2020).

Policies on Accelerating the Construction of 5G Networks, Sihui Industry and Information Technology Bureau (2021); Notice on Accelerating the Construction and Application of 5G networks, Puyang City Government (2020).

Guidance on the 2019 Construction of the Information and Communication Industry and the Rectification of Work, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (2019); Beijing's Commercial Building Broadband Monopoly Governance Work is Beginning to Take Shape, PRC Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (2020).