What's in a Tech List?

Technology Priorities and the Destiny of Nations

Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP). Welcome to the 2-2-2, our monthly newsletter which aims to provide you with regular, thought-provoking perspectives from our team and outside experts as we chart a path forward for our country to maintain global leadership on key technologies that will shape our future.

What’s in a Tech List?

Edition 4

In this month’s edition of 2-2-2, Senior Advisor PJ Maykish, Associate Director of Research and Analysis Abigail Kukura, and Research Assistant Asher Ellis analyze lists to answer the question of which technologies will extend U.S. national competitive advantages.

In his 1620 magnum opus on scientific revolutions, Novum Organum, Sir Francis Bacon wrote that “we should notice the force, effect, and consequences of inventions.” Printing, gunpowder, and the compass “changed the appearance and state of the whole world… first in literature, then in warfare, and lastly in navigation.” The impact was so immense “that no empire, sect, or star, appears to have exercised a greater power and influence on human affairs.”

We know, as Bacon did, the power of technologies to shape the destiny of nations. In today’s global strategic competition, the choices leaders make about tomorrow’s tech might be their highest stake bets. SCSP believes the United States needs a plan to invest in, develop, and harness the critical technologies of the future. But how does one predict let alone prepare to lead in tomorrow’s tech? The 21st century answer begins by making a list. Hundreds of organizations including at least 17 governments, multiple U.S. government agencies, banks, universities, venture firms, think tanks, and even crowdsourced wikis publish “lists” of emerging technologies they think matter most. SCSP identified 78 lists published in the last five years by dozens of entities in the United States and around the world.1

The 39 lists from U.S. government or non-government entities represent visions of the world viewed through the authors’ respective lenses. None, however, represents “the list” for U.S. national advantage that captures a whole-of-nation perspective—both public and private—on where technology is going to inform stakeholders where to direct resources. The Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community lists rightly focused on their own missions and capabilities, while the White House National Science and Technology Council’s Critical and Emerging Technology List Update represents the wider government perspective but is not designed to drive policy development or funding or shape private sector activity. Lists generated in the private sector tend to revolve, understandably, around business opportunity and lack a larger national competitiveness lens. The absence of a comprehensive list, combined with misalignment between the government and the rest of the innovation ecosystem leaves the United States susceptible to trailing in the next strategically important platforms—just as it did in 5G.

Analyzing these lists can help begin to answer the question of which technologies will extend the United States’ national competitive advantages. By holding a stethoscope to different ecosystems’ priorities, we can glean insights into what a “list of lists” could look like that transcends parochial interests and reflects the nation’s interest in its broadest sense. We can see the gaps between government and non-government priorities that need filling. And by comparing lists across the world, we can begin to identify how other governments are weighing their own strategic technology choices and consider our own vulnerabilities and strengths, as well as the power of our alliances.

United States

Four of the top five technologies are identical across lists produced by the U.S. government and non-government entities (including venture capital firms, corporations, think tanks, and consulting firms): Artificial Intelligence (AI), Biotechnology, Energy, and Autonomy/Robotics. However, U.S. government and non-government lists differ in the following ways:

Blockchain rounded out the top five areas of interest for non-government sources, but did not make the government's top 20 in prevalence.

Meanwhile, Space was among the top five technologies in government sources, but did not make the top five for non-government. Yet looking at lists alone could suggest that space is receiving less attention from the private sector, when in reality the U.S. commercial space sector is thriving, in part as a result of government signaling and incentives. The synergy between government and non-government on space technology suggests the powerful potential of public-private collaboration.

A note on Biotech: One might posit that the uptick in biotechnology interest across both government and non-government is solely a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, roughly half of biotechnology references were related to synthetic biology/computational biology/biomanufacturing and not directly related to vaccines or health, suggesting biotech is not a passing priority.

What does this tell us? The U.S. private sector appears significantly more energized and likely ahead of the government in investing in, developing, and applying Blockchain, a sector that could transform fields as diverse as supply chain management, scientific research, voting systems, and the architecture of the internet. The Biden Administration has begun to study and states have begun to legislate on blockchain, but the government’s ability to shape the development of and benefit from blockchain could lag. It will depend on industry for the evolution of the ecosystem, while other countries could choose a more deliberate course.

U.S. Startup Unicorns Edging Towards Broader National Priorities. Beyond lists, the number of ”unicorns” (a startup company with a value of over $1 billion) provides insights about alignment between government and private sector priorities. Since 2017, startup activity in the United States has shifted into some technology categories that align with government priorities, such as AI, Cybersecurity, and Data Management. Yet the startup space is still dominated by less resource intensive technologies such as Internet Software and Fintech, while resource-intensive government priorities like Computer Hardware continue to lag behind other emerging industries despite growing overall. Even the commercial space industry, despite growing rapidly in response to government signaling and through public-private-partnerships, remains a difficult arena for startups to break into.

Source: Data from CB Insights “Complete List of Unicorn Companies”

China

China, meanwhile, has translated lists into strategy. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that gunpowder, printing, and the compass are three of the “four great inventions” celebrated by China (the fourth is paper) in its national narrative and are also the ones that Francis Bacon saw as “immensely impactful” in 1620. Appearing to channel Bacon, Xi Jinping remarked in 2014: "History has taught us that a country's strength is not defined by its economic size, population, or territorial mass. [China] has been beaten because we fell behind in technology; we must insist on becoming a technological powerhouse." This belief has animated Beijing’s policies for nearly two decades. Haunted by the fact that China’s Century of Humiliation was in part the result of a failure to keep up with Western technology, China acted to bolster its emerging technology capabilities nearly a decade before Western capitals awoke to today’s technological moment.

Beijing has focused on emerging technologies since 2006. Since issuing its “Medium-to-Long term Plan for S&T development” (MLP) in 2006, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has followed up with numerous technology strategies including: Strategic Emerging Industries in 2010, Made in China 2025, and the 12th, 13th and 14th Five Year Plans. Each document calls out specific technology areas and further refines Beijing’s S&T ambitions (for a timeline depicting the PRC's S&T plans, click here). Over time, these plans have grown in scope and ambition. While the MLP was primarily focused on improving China’s ability to innovate, Made in China 2025 and the 14th Five-Year Plan emphasized not only innovation but also the need to promote convergence between these rapidly developing fields, the need to move China’s economy up the value chain, and the need to build an indigenous technology stack across key industrial sectors so that China is not reliant on the West.

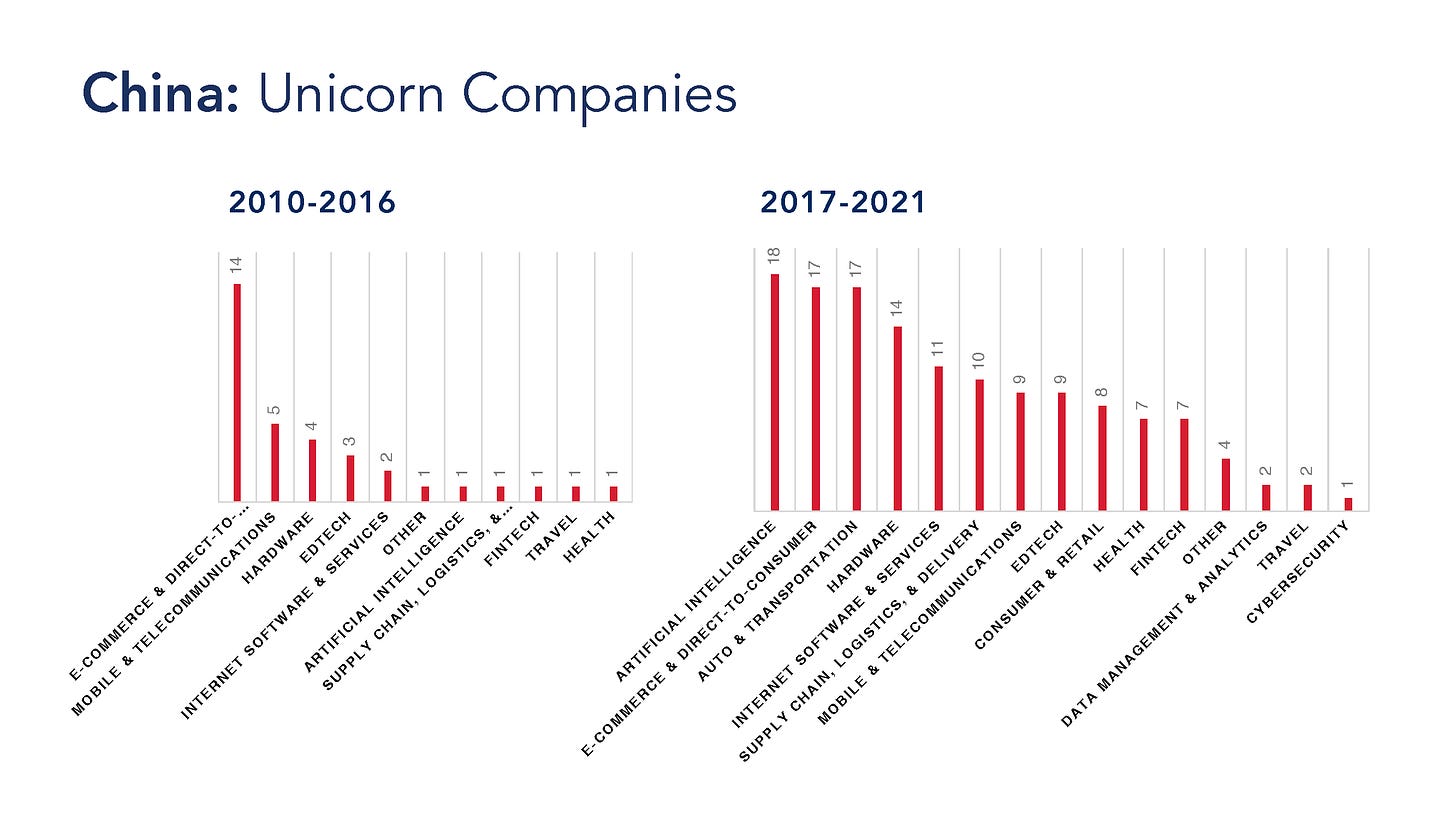

A Whole of Nation Approach to Tech Development. Beijing uses laws and regulation, national incentives, and messaging to align the private sector with its strategies. One way to measure its success is by looking at China’s booming tech unicorns. Our analysis of data on PRC startup valuations shows that in China, state direction and identification of strategic technology sectors is taken seriously by startups and appears to have an impact on their valuations. From 2010-2016, most Chinese unicorns were in: E-commerce, Telecom, Hardware, and Edtech. By 2017-2021, after the release of Made In China 2025 and the New Generation AI Development Plan, top PRC unicorns shifted to AI, Autos, E-commerce, and Hardware. However, just as state direction can give, it can also take away: Edtech will probably fall off the 2022 unicorn chart given recent regulatory backlash.

Source: Data from Complete List of Unicorn Companies, CB Insights (2022).

Allies and Partners

More than a Two Player Game. Many innovators, startups, and larger businesses are riding the innovation wave outside of the United States and China. The fact that so many are located in countries that are key U.S. allies and partners, presents an opportunity to coordinate tech priorities and create new democratic tech alliances.

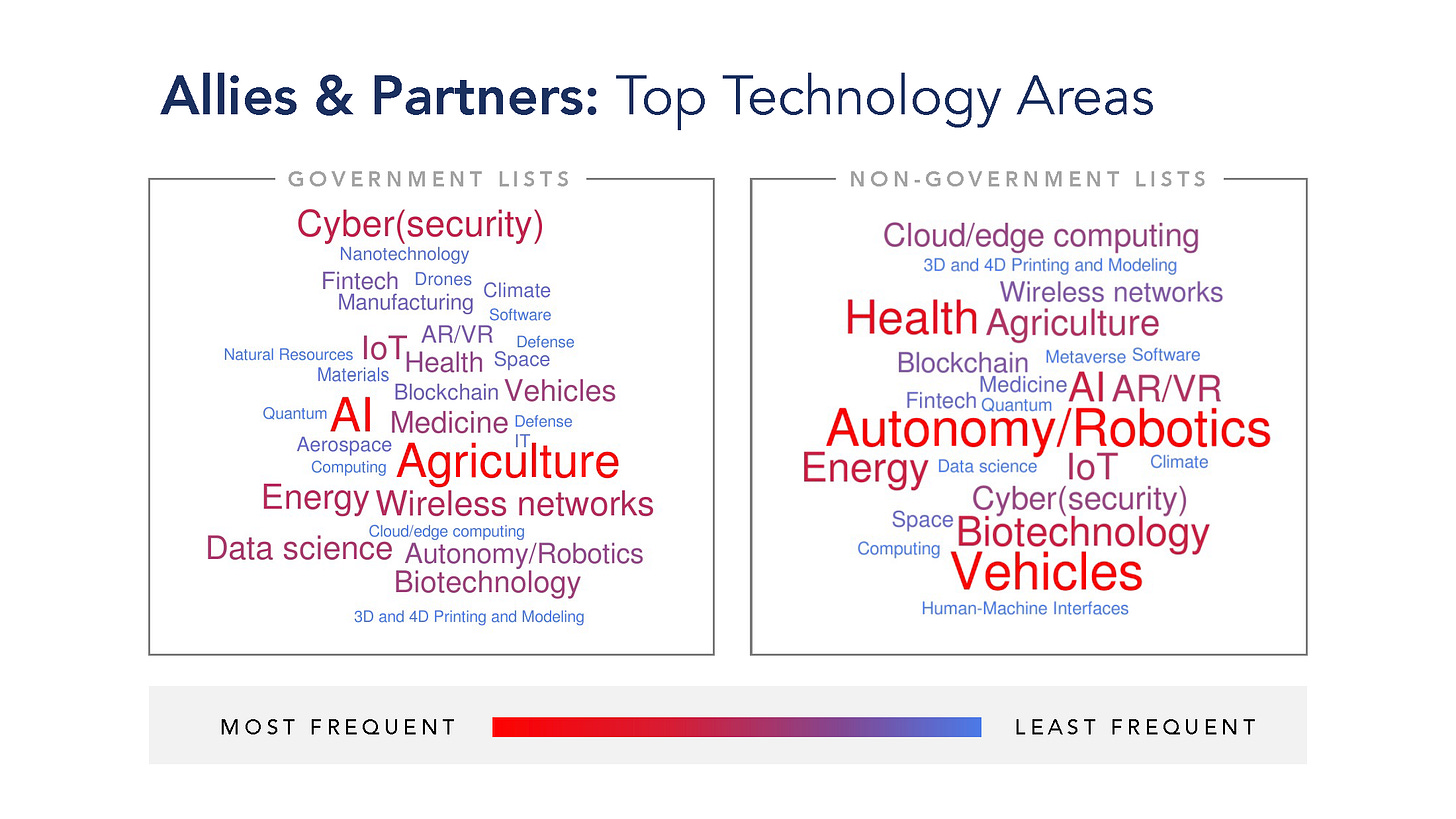

We analyzed 39 reports published since 2017 from various ally and partner governments and private sector organizations about emerging tech. Among those reports were 15 governments that have issued technology strategies or conducted horizon scanning exercises to inform their technology policies.2 The most commonly mentioned technologies in this sample of ally and partner reports were AI, Agriculture Technologies, Cyber(security), Autonomy/Robotics, and Vehicles. Similar to the United States, there was both overlap and apparent differences between government and non-government reports.

AI was among the top five most cited technologies on both government and non-government lists. Yet government lists more frequently included Agricultural Technology, Cyber(security), Wireless Networks, and Energy, while non-government lists more frequently included Vehicles, Health, IoT, Biotechnologies, and Autonomy/Robotics.

Similar to the United States, allied and partner governments may be underestimating the impact of technologies like Biotechnology that their private sectors are prioritizing, while private sectors may not be sufficiently incentivized to focus on government priorities like Agricultural Technologies.

Limited Ally and Partner Unicorns in Emerging Tech Areas. The number of unicorn startups has increased significantly since 2016, the majority of which focus on Fintech. Significantly fewer have emerged in key government priority areas such as AI, Agriculture, and Autonomy/Robotics, suggesting that the public and private sectors have not necessarily aligned either on lists or in valuations.

Source: Data from Complete List of Unicorn Companies, CB Insights (2022).

Conclusion

Nations and their leaders are faced with the dual challenge of declaring priorities (an issue identified in the NSCAI’s Final Report), and marshaling their public and private ecosystems to realize those priorities. Countries have pursued different organizational approaches to the challenge. China and, to a more limited extent, our allies and partners (such as the UK and Japan), have formal entities responsible for studying the public and private sectors and conducting technology horizon scanning on behalf of their nations. America has taken a more decentralized approach. It has not yet tapped its vast technology horizon scanning talent across academia, industry, and government for national purposes. Given the changing strategic and tech landscape, the effort should begin in earnest. The government, venture firms, banks, universities, think tanks, and companies would all benefit from forums that bring them together and incentivize them to think and plan together on technology strategy for the nation’s benefit.

Turning lists into strategies matters. The nations that effectively organize to develop and deploy new technologies on a global scale will shape their own destiny and world order. China invented the compass, printing press, and gunpowder, but Europe deployed them to greater effect, ultimately leaving China a century behind. As American historian Lynne White wrote, “The acceptance or rejection of an invention, or the extent to which its implications are realized if it is accepted, depends quite as much upon the condition of a society, and upon the imagination of its leaders.” Today, China is learning from its past – developing strategies to harness new technologies. It is time for democracies and their private sectors to pool their competitive advantages in partnership, and map a tech future together.

Last month, SCSP announced a Call for Engagement.

The call aims to answer the question of: “How can the United States and allies and partners better deter authoritarian aggression in the Western Pacific and Eastern Europe?” Specifically:

What low-cost techniques that could be implemented in 2-3 years might strengthen deterrence?

What strategies might the United States pursue that preserve our vital strategic interests more effectively than deterrence?

What does the United States get wrong about deterrence, including its relevance as a concept, how emerging technologies are changing the nature of deterrence, or how different cultures perceive deterrence differently?

From May 2 to July 29, 2022, SCSP will accept submissions in the form of a short paper or video answer to the prompt. Up to 3 entries will be selected to be published in the SCSP Newsletter, 2-2-2, as well as on the SCSP website, and SCSP will offer the authors of the three submissions $2,000 respectively. The authors of the selected submissions may also have an opportunity to brief the SCSP Board of Advisors.

Starting on May 2nd, visit our submissions page to learn more and upload your submission.

Our methodology to compare these ecosystem priorities was to count the number of mentions of a given technology as an indicator of interest in technology areas (click here for additional details on our methodology and sourcing).

Since 2017, at least 15 countries and the UN have issued strategies or plans on how to harness emerging technologies: UK, Australia, Canada, Japan, Taiwan, Switzerland, Sweden, France, India, Israel, New Zealand, Ukraine, Singapore, Poland, and South Korea.