Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this edition of 2-2-2, SCSP’s Liza Tobin, Channing Lee and David Lin decode underlying messages in PRC propaganda.

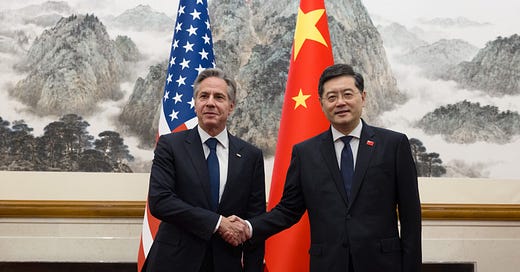

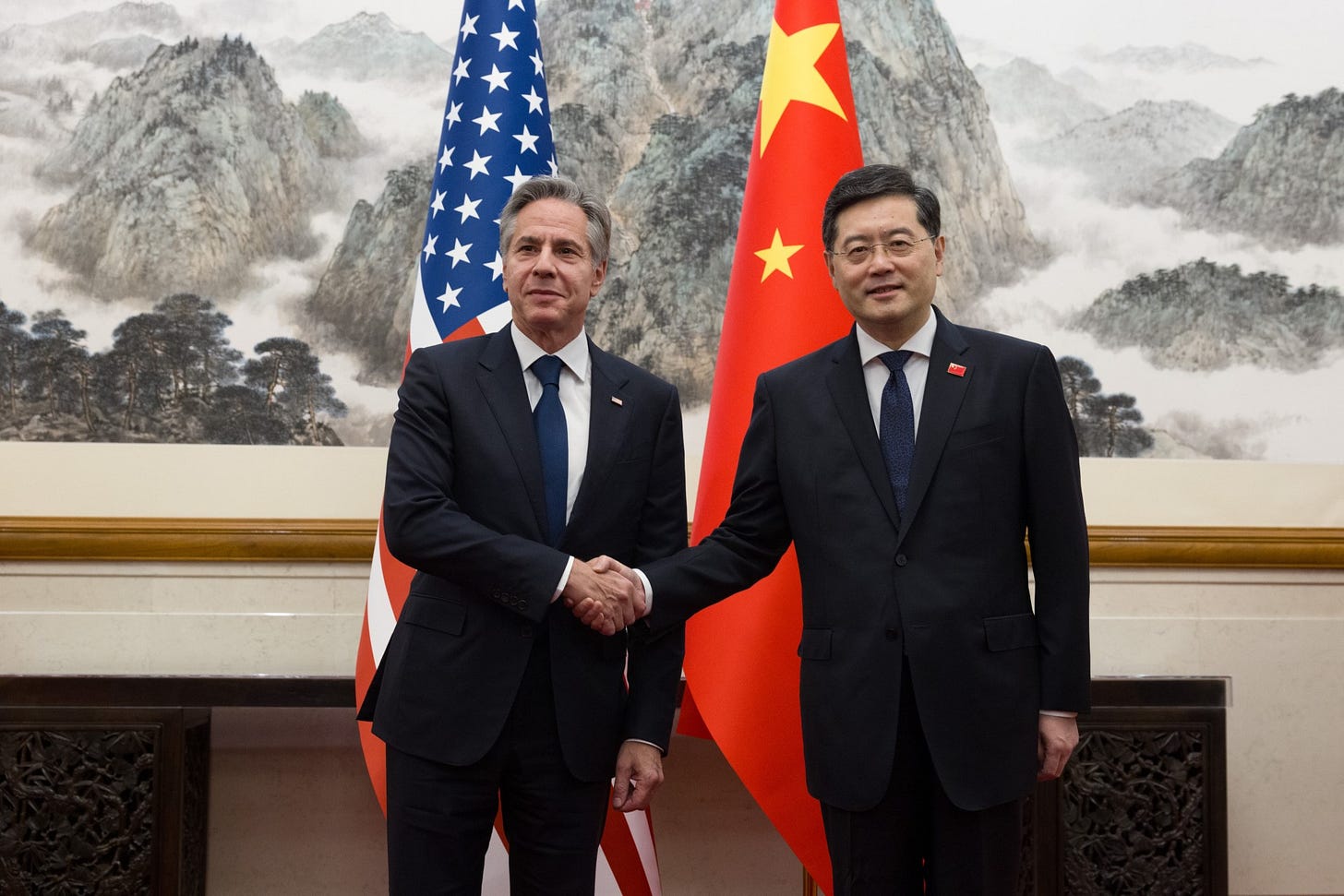

Since the People’s Republic of China (PRC) re-opened after COVID lockdowns early this year, a steady stream of senior U.S. officials, foreign leaders, and corporate executives have traveled to China or sought other face-to-face engagements with PRC counterparts.1 The U.S government has emphasized that “intense competition requires intense and tough diplomacy.” Both government and business leaders likely aim to use face-to-face meetings to strengthen their competitive edge in their respective domains and provide a degree of stability amid geopolitical tensions.

More important than the meeting itself, however, is understanding the context and leveraging it for national or business advantage. U.S. and PRC diplomats famously battle over every detail of protocol for these meetings, from negotiating the right government level under which to conduct a meeting, to the logistics surrounding the stairs to plane and deplane from official aircraft. These dynamics are not new: decades of experience negotiating with the PRC since the 1970s should make Americans cognizant of Beijing's skill shaping optics and narratives and wary of taking its words at face value.

A Chinese slogan that became popular in the Mao era — 实事求是 (“seek truth from facts”) — captures the need to test theory against reality. During the PRC’s early years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) invoked the phrase to push its version of the “truth” – with tragic results in the form of mass starvation and poverty. Such narrative engineering continues today, as the CCP twists language to revise history and shape public opinion both inside and outside China. Foreign interlocutors encounter this in meetings with PRC diplomats and executives who, regardless of personal views, must adhere to the CCP’s constructed and approved narrative – the “Party line” – and even demand that foreigners do likewise.

Those who pursue dialogue with the PRC would do well to do their own version of “seeking truth from facts.” Learning to spot and interpret common CCP propaganda tropes can help foreign interlocutors avoid falling into traps and developing unrealistic expectations. After all, CCP propaganda is not only directed at PRC citizens – its target is global.

Here are some frequently-used CCP expressions of the “truth” – alongside our effort to decode the underlying message:

Cabinet-level visits and meetings this year include National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s meeting with foreign minister Wang Yi in Vienna in May, CIA Director Bill Burns’s visit to China the same month, Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit in June, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s and Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry’s visits in July. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo recently announced she intends to visit China from August 27-30. U.S. tech executives visiting China this year have included Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and Pat Gelsinger.