Hello, I’m Ylli Bajraktari, CEO of the Special Competitive Studies Project. In this last edition of 2-2-2 for 2022, I reflect on some of the key issues related to national security this year that were impacted by the role of technology.

Let me begin by thanking all our subscribers for following our work over the last 12 months. As we reflect on the past year, we would like to share the presentation materials that we use for our engagements and discussions with different stakeholders – in the United States and abroad – to outline the Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness (our first major report published in September 2022) and the subsequent Interim Panel Reports (IPRs) we have published over the past few months. Many thanks to Steve Blank for his feedback on our products.

On January 4, tune in anywhere you get your podcasts for our new series NatSec Tech. Every two weeks, Jeanne Meserve will host a series of guest expert conversations on topics ranging from how artificial intelligence impacts students in school, how synthetic labor impacts the workforce, the impact of export controls, and more!

I value the dialogue we have had over this past year and would like to continue our conversations on technology and national security. Please send us your feedback, criticisms, and suggestions.

Key Takeaways from 2022:

Technology and national security intertwined in crucial ways across three major arenas in 2022: (1) the Russian invasion of Ukraine, (2) policies to increase domestic capabilities, and (3) the emergence of new technologies that promise to reshape our societies and economies.

Technology: A Key Component of the Ukrainian War Efforts. As we noted in our Intelligence newsletter, United States Government (USG) efforts to publicize Russian plans leading up to the crisis were vitally important. The U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) successfully warned the White House, Ukraine, and its allies of the Russian invasion months before its actual occurrence. Early and rapid declassification of U.S. intelligence allowed policymakers to “prebunk” and counter Russian disinformation, undermine potential false flag operations, discredit the Kremlin’s narrative, and strengthen the allied response.

At a macro level, the invasion has reshaped the European security landscape, but at a micro level, we see how technology played a critical role in the conflict, as Ukrainians adopted and used off-the-shelf capabilities in very creative ways to counter Russian military aggression. In what SCSP Chair Eric Schmidt called “The First Networked War,” we saw how the application and adoption of commercial space, AI, cyber, and UAV technology played a critical role by enabling Ukrainian communications and intelligence for military operations. It was not only the IC that was able to alert the movements of the Russian forces towards Ukraine. Private sector companies – from small AI startups involved in predictive analytics such as Rhombus to large satellite imagery companies such as Maxar – tracked the movements of the Russian military in real time before and during the invasion. We expected drones to feature prominently in the conflict in intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR) missions, as strike platforms, and as munitions themselves. But the pervasiveness and diversity of their use across domains surprised us as Ukraine became a theater of operations for UAVs sourced from around the world, with Chinese, Russian, Ukrainian, Turkish, and Iranian drones demonstrating increasingly powerful capabilities.

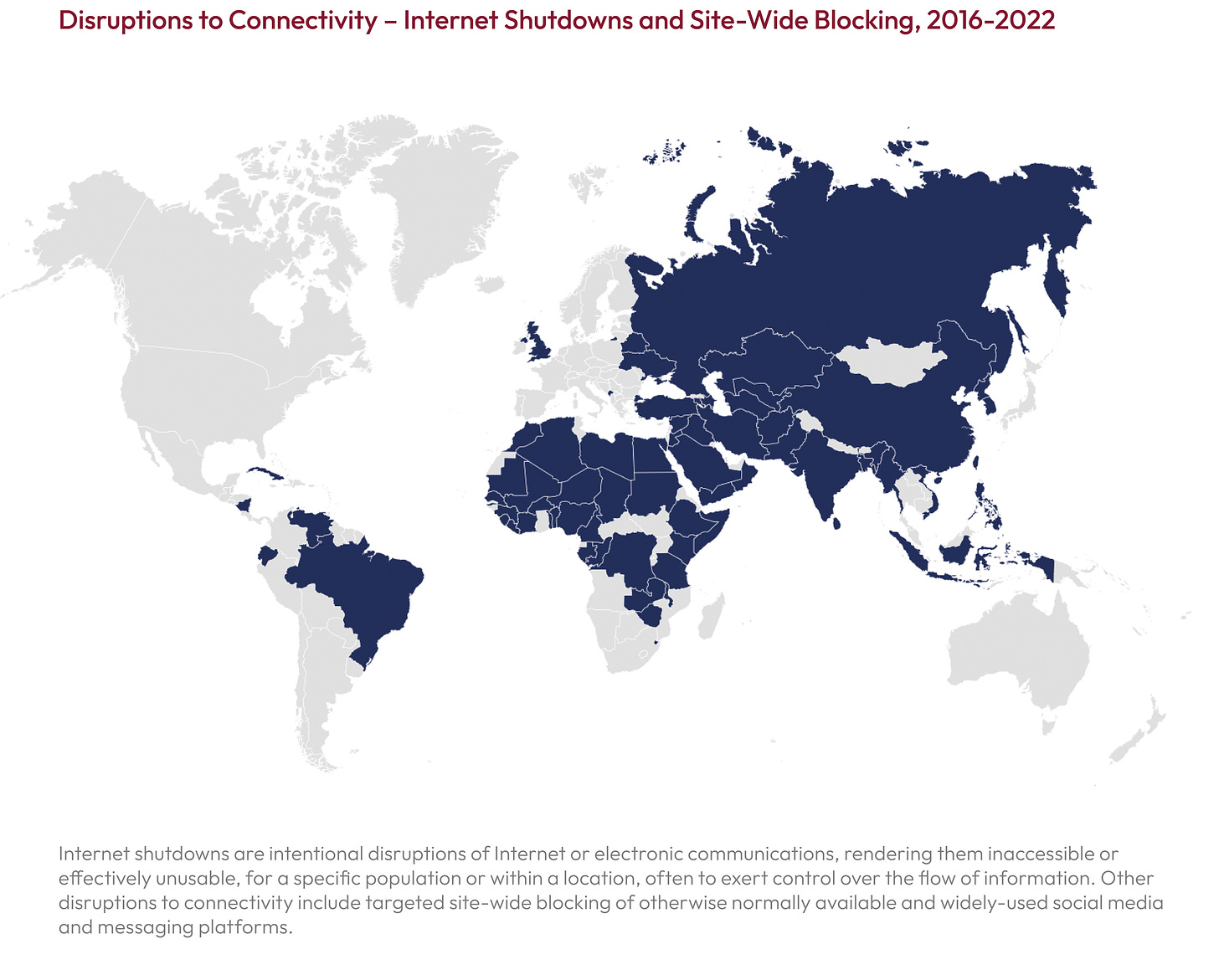

Lastly, as we noted in a recent newsletter and our Foreign Policy Interim Panel Report, the war against Ukraine has clarified the centrality of Internet connectivity to a nation’s sovereignty; reminded the world of the potential of a tech-enabled democratic society to provide basic government services; and demonstrated the central role of information and communications technology (ICT) companies in protecting against cyberthreats, providing platforms for digital services, and countering dangerous Russian-backed disinformation and cyber attacks. These are vital dimensions of how Ukraine is persevering in a conflict against a vastly larger adversary.

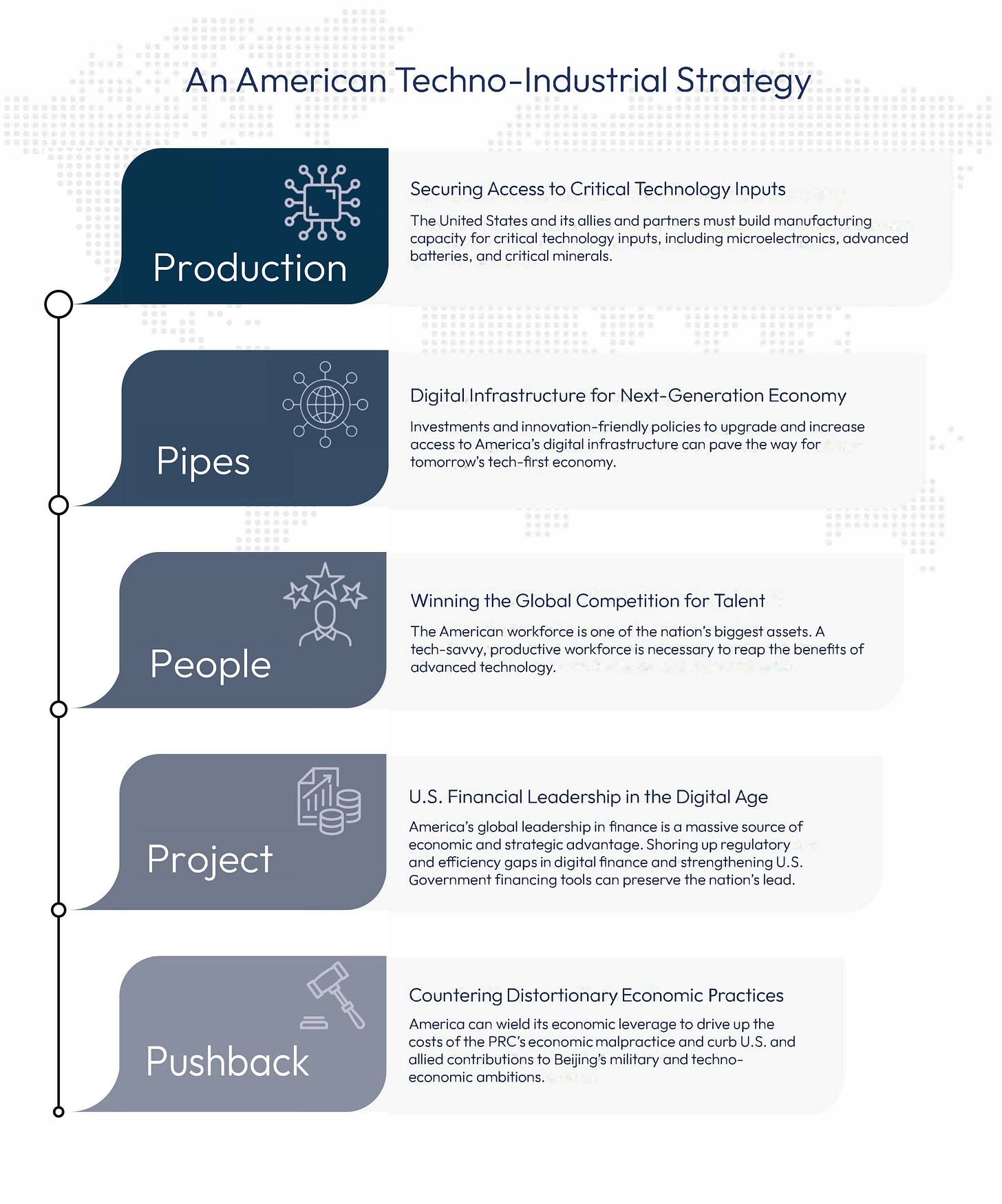

Tech Competition with China Gets Real (and Resourced). In 2022, we saw major policy shifts aimed to rebuild America’s techno-economic foundation, as well as moves to prevent Beijing from accessing U.S. technologies. Congress passed and the President signed into law the CHIPS and Science Act, a landmark bill previously thought impossible. Investments in American industry and technology in this legislation, in addition to other investments passed by Congress this year (i.e. provisions included in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), could reach over $1 trillion in aggregate. Furthermore, initiatives included in the $1.7 trillion omnibus spending bill, which includes $858 billion for defense, would further strengthen the nation’s investment in emerging technologies. SCSP has argued that the United States needs a techno-industrial strategy to connect emerging policy efforts in Washington with new ideas and partnerships with the private sector, providing a game-changing boost to the U.S. technology and innovation ecosystem while creating better and more jobs and strengthening manufacturing hubs across the nation. This year’s series of landmark legislation is a strong start, but translating these investments into upgrades to U.S. industry and technological competitiveness will depend on effective implementation and diligent oversight.

In addition to investing in domestic capabilities, 2022 also saw significant moves to restrict Beijing’s access to advanced technologies. As National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan first noted at our Global Emerging Technology Summit in September, the United States must “maintain as large of a lead as possible” in strategic sectors. In early October, the Biden Administration announced new export controls to restrict the flow of leading-edge semiconductors (and the critical tools, components, and expertise used to make them) that power the PRC’s military modernization, AI ambitions, and tech-enabled surveillance. It was the Administration’s most significant actions to date to address PRC technology threats.

AI and Other Emerging Technologies Continue to Make Breakthroughs. 2022 saw impressive capabilities demonstrated by AI-enabled platforms almost daily. AI progress continued its steady march with advances such as AI models beating humans in Diplomacy or learning how to play Stratego, while DALL·E 2 (image) and ChatGPT (text) models demonstrated the immense potential of applying generative AI to creative tasks that were previously the exclusive domain of humans.

Our September Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness report included a “Ghost Chapter” that illustrated the state of LLMs today. We wanted to know what these models had to say about the evolving techno-economic competition between the United States and China. So we asked three LLMs to weigh in on some of SCSP’s key framing questions. While the responses did not generate any novel insights, they were generally accurate and informed. This exercise was perhaps an early indication of how knowledge workers will increasingly be aided by AI tools in the coming years.

Six Things to Watch and Complete in 2023

The year 2023 provides an important opportunity to solidify some of the tech-centered national security policies and strategies that will position the United States and our allies and partners for the rest of the decade. SCSP has noted that the window between now and 2030 will be the period of maximum risk for confrontation with Beijing for a variety of reasons, including Taiwan tensions, PRC economic headwinds, and China’s ambition to lead the world in AI by 2030. Therefore, 2023 is the critical time for the USG to build a tailor-made budget to mitigate any threats we may face from China during the later part of this decade. Here are six moves needed to get there:

Capitalizing on Partnerships: The Ukraine crisis has demonstrated what private-public alignment among and within democratic nations can achieve during times of conflict. As we noted in our newsletter at the outset of the crisis, the United States should recognize — and seek to leverage — the ways in which the actions of major tech firms can advance or coincide with the national interests of the United States and its allies. Such public-private efforts will be central to other contingencies that may arise in the future, especially those around Taiwan.

In addition, the United States has reinvigorated alliances with new initiatives, including AUKUS, the Quad’s Technology, Business, and Investment Forum (QTBIF), and the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC). Next year provides an opportunity to cement these initiatives and make further progress. This year, for example, the TTC helped achieve a breakthrough in transatlantic data sharing. However, the agreement faces legal hurdles and there is a need to accelerate progress on some issues to avoid losing the momentum. SCSP has argued that all these partnerships need to be brought together under a DemTech Alliance framework, to forge an allied approach to technology competitiveness.

Furthermore, the United States and its allies and partners will also need to move towards developing a robust export control regime for emerging technologies, strengthening enforcement of existing guardrails, and screening outbound investments to prevent democracies’ capital and know-how from supporting Beijing’s military modernization and AI ambitions. The DemTech agenda can craft a model for alliance cooperation that pools democratic capabilities and advantages, allowing us to better compete against the organizational model and scale of resources that the PRC brings to the competition.

Harnessing Open and Commercial Sources to Enhance Intelligence Capabilities: The war in Ukraine is the latest iteration of how open source intelligence (OSINT) “has proven itself over and over,” as noted by the CIA’s Chief of Community Open Source Patrice Tibbs. Yet, the exponential growth in publicly and commercially available information is most certainly outpacing the IC’s current capabilities — or anyone’s for that matter — to fully harness open source in support of U.S. decision making and policy. In contrast, China highly values the insights it can derive from OSINT and has an “estimated 100,000 analysts tasked with scouring scientific and technical developments globally, mostly in the U.S.”

The United States can no longer afford not to harness the full potential of publicly and commercially available information. The 2022 National Security Strategy took the first step in calling on the IC to adapt organizationally by better integrating open source materials. Such a significant change, however, will require sustained focus from the White House, Congress, and IC leaders.

The next critical step would be for the USG to create a new and well-resourced institutional home for open source collection, acquisition, processing, and analysis. As our SCSP friend and advisor Dr. Amy Zegart argues powerfully in the most recent issue of Foreign Affairs, “developing U.S. intelligence capabilities for the twenty-first century requires building something new: a dedicated, open-source intelligence agency focused on combing through unclassified data and discerning what it means. Creating a 19th intelligence agency may seem duplicative and unnecessary. But it is essential.”

One of the primary objectives of such an agency, we argued in our Intelligence Interim Panel Report, should be to build the data architecture, computing power, and AI-enabled tools to collect and process publicly and commercially available data at scale. We also outline the attributes that a new open source entity should have in order to meet the USG’s needs, such as: broad dissemination authorities, subject matter expertise, a voice within the IC, publishing rights for its products, a clear mission, and an institutional structure that allows it to act as a gateway for open source information between policy agencies, the IC, and external actors.

To demonstrate an example of the work this agency could do, we produced an analysis emulating the style of a Presidential Daily Brief — the premier intelligence product that is delivered to the President every day — but drawn from open-source information. This type of two-sided analysis is difficult due to legal, cultural, and organizational constraints. Comparing tech sectors between the United States and the PRC is a classic example of this dilemma.

Such tech-specific comparisons are particularly difficult for the USG to produce currently because so much of the progress takes place in the private sector, far from the focus and authorities of traditional intelligence analysis. Yet, such comparisons are essential for effective policymaking. The data needed abounds from academic papers to corporate reports and economic statistics. Our analysis represents a snapshot in time as the two largest economies in the world compete in rapidly evolving strategic technology sectors. The broader point is that to build a long-term competitive strategy, the United States needs comparative technology analysis which begins solving the traditional barriers to performing such two-sided analysis. Simply put, our leaders need to know where we are in the competition in order to guide strategy and move resources – to be proactive and not reactive vis-a-vis the PRC.

The Future of Warfare Is Happening Now — We Need to Move Faster: The character of warfare and peacetime is changing under pressure from three key drivers: (1) advanced and emerging technologies, including AI, (2) innovative operational concepts for employing those technologies, and (3) intensifying geopolitical rivalries. We already see attributes of this new character of conflict in Ukraine — near-ubiquitous sensing; inability to hide, surprise, or amass forces; a strong temptation to pre-empt or risk being annihilated; and strong disinformation tools that compound the fog of war. Because of these changes, as SCSP’s Eric Schmidt and Bob Work argued in their recent Atlantic piece, the competition between the United States and China (as well as Russia) is entering a phase of persistent conflict below the level of armed clashes. The risks of a hot war are increasing, and should such a war occur, its impact on Americans would be unlike any in our nation’s history.

But is the United States moving to adopt and change at scale? The U.S. military, particularly the Marine Corps, has continued to reorganize and invest in distributed operations that play to its enduring strengths. This was one of the core tenets of the Offset-X strategy proposed by SCSP. It has been further validated by the Ukrainian military’s successful use of distributed, network-based operations against Russia’s hierarchical forces. We have also seen CENTCOM’s Task Force 59 move to experiment with and use human-machine teaming. The Air Force is also pursuing drones that will serve as “loyal wingmen” for its fighter aircraft, capitalizing on the potential of human-machine teaming for high-risk missions. We argued that human-machine collaboration and teaming is something that the U.S. military must integrate into every aspect of its operations in order to master the sensing, decision-making, and execution requirements of the emerging character of conflict. Additionally, the Pentagon created the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office to enable digital transformation of the Department of Defense, and enable the use of AI and emerging technologies. Several COCOMs have followed suit, creating positions and teams to deal with data, AI, and disruptive technologies. This digital transformation will be essential to pursuing software primacy – which we argued will be the greatest determining factor of military strength in the future.

While these changes are essential to U.S. military primacy, the Ukraine conflict has also exposed vulnerabilities we have in the defense industrial base. The speed and intensity of operations — which would most certainly be even higher in the Indo-Pacific region — has stressed, if not outstripped our current ability to produce and stockpile munitions, platforms, and expertise.

Techno-Industrial Strategy Tested: America's emerging approach to promoting and protecting its technology advantages will be tested in at least three areas in 2023. The first is the implementation of the CHIPS and Science Act. In February, the Department of Commerce is expected to release a request for applications for CHIPS funding, from which loans and grants will be awarded. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has said that she hopes some funds will be awarded by spring 2023. CHIPS implementation will receive heavy scrutiny from taxpayers, lawmakers, and the private sector, and even allies and adversaries. Any indication of success or failure will be held up as an indicator of America’s ability to execute industrial strategy, determining whether large-scale investments in technology competitiveness will be politically palatable or poisonous.

As noted above, the second area to watch is U.S. efforts to slow down China’s progress in advanced technology via guardrails like export controls and a new outbound investment screening mechanism that could be unveiled in the new year. The effectiveness of the October 7, 2022 export controls will hinge in part on whether Japan and the Netherlands join the United States in blocking PRC access to critical equipment to manufacture advanced chips. On investment screening, the White House has been working over the past year on a new mechanism designed to restrict U.S. investors from supporting China’s technological advance at the expense of American security. It will have real teeth if it includes power to block or mitigate investments of concern, rather than simply requiring companies to disclose their plans to the government.

A third area where American industrial strategy will be put to the test is in the unfolding battle over advanced networks. As the 5G race now enters its second round, U.S. stakeholders must drive domestic innovation of 5G applications that will breathe life into advanced networks beyond just faster download speeds – economic blockbusters like smart manufacturing, smart grids, and AI-managed logistics systems. America should ensure that significant telecoms spending and incentive packages foster rapid diffusion of and security of these applications to benefit Americans, guided by an overarching digital infrastructure strategy.

Internationally, the USG must accelerate its support for trusted 5G technology while adopting a more comprehensive, strategic approach to digital infrastructure beyond 5G. A full-stack approach should build on areas of U.S. advantage (where China is racing to catch up) – cloud computing and “offsets” like satellite-based connectivity and open and virtualized networks, bundling those elements with 5G technology from allies. Next, America must strengthen its toolkit to structure and finance tech export, investment, and aid packages to build secure, trustworthy digital infrastructure in emerging and developing economies. An enlightened American approach to advanced networks means that China’s loss can be our allies’ and partners’ gain: USG bans on PRC-origin telecom equipment create market opportunities that American and other non-PRC firms can fill with reshored and friendshored production. To ensure that democracies, rather than Beijing, invent the digital future, the United States must lead allies and partners in setting emerging standards for 6G. The current, geographically fractured approach risks ceding 6G leadership to Beijing.

Next Generation Platforms – Start Now with Action Plans: As the international competition over the next wave of emerging technologies heats up, the United States needs to act now to develop technology action plans in the six key sectors we identified to ensure that we do not get “5G’d” again. The three key battlegrounds discussed above – AI, microelectronics, and 5G – will themselves continue to evolve, with AI reaching new frontiers and novel computing paradigms, such as Quantum and next generation networks on the horizon. Additionally, the three technologies that will create the next wave of general purpose innovation are: biotechnology, energy storage and generation, and areas where the preceding technologies converge, like smart manufacturing.

Biotechnology: The imminent stand up of the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology portends an even greater level of policymaker interest in ensuring U.S. leadership in this field, which the private sector and academia see as long overdue. We have the opportunity to help frame the issue, provide a strategy, and improve policymaker literacy on biotechnology by helping them recognize that its potential extends beyond just health. Biotech is becoming a focal point of the competition.

Quantum: IBM’s public quantum computing timeline includes ambitious goals it set for 2023, including quantum advantage in select applications, along with a 1000 qubit machine. Meanwhile quantum computing startups continue to make progress with novel architectures. To date, China has repeatedly announced similar progress soon after a U.S. team unveils its research. It remains to be seen if this trend will continue in 2023. The passage of the Quantum Computing Cybersecurity Preparedness Act last week underscores the need to begin the work of deploying post-quantum cryptography standards in the coming years.

Energy: Fusion energy had quite the year in 2022. Policymakers showed renewed interest in the decades-old endeavor of generating the power of the sun on earth, calling for a bold decadal vision and designating a Department of Energy fusion lead coordinator, while commercial fusion companies continued to raise record-breaking funds. Then, in December, scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory achieved ignition – a major milestone demonstrating fusion’s scientific feasibility. All of this progress underscores the need for a forward-leaning action plan to bring fusion to the grid sooner than the multi-decade timelines currently projected. The recently passed IRA may also provide much needed stimulus to new energy and climate mitigation moves.

We need to get AI and Data Governance Right – 2023 Is the Time To Do It: Societal strains and inconsistencies combined with suppression of independent voices in authoritarian regimes illustrate the strengths of democracies and the need to protect them. The importance of the consent of the governed, the criticality of an open society, and the role of an independent civil society has been made very clear this year; technology and technology governance help protect and enhance these key foundations.

We need to do four things to ensure justified confidence in AI and other emerging technologies, govern use cases and outcomes by sector; empower and modernize existing regulators to address regulatory challenges posed by emerging technology; focus technology governance on high-consequence use cases; and strengthen the U.S. non-regulatory ecosystem.

Additionally, on the data front, the free flow of data – with appropriate safeguards for privacy and security – is the logical extension of the larger American project of encouraging the free flow of goods, ideas, and people. We need to leverage our collective public and private data assets for our nation’s benefit. As we note in our recently published report, the absence of an executable whole-of-nation data strategy that includes federal privacy legislation has left the United States at a competitive disadvantage.

The EU has made significant headway to craft an approach to data governance with a heavy emphasis on regulation. The EU’s regulatory frameworks, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that went into force in 2018, the 2022 Digital Services Act package, and the draft European Data Act, are establishing precedents that impact the global collection and use of data. The longer the United States delays establishing its own data governance approaches, the greater the divergence between America’s policy void and the EU’s highly regulated approach will become. This will leave a vacuum for other nations to fill with governance models that have global influence and do not align with U.S. interests and values, or allow for fragmented global data governance. The United States and the EU also need to find ways to coordinate their data governance efforts.

On the American side, we need to build upon the data governance efforts of Congress and the Administration. An important step in establishing comprehensive data privacy legislation requires drawing on the good work of the bipartisan American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) introduced in the House in June. Ultimately, comprehensive, national privacy legislation would address the arduous patchwork of state privacy laws that currently leaves many Americans’ data vulnerable, businesses with regulatory uncertainty and costly compliance measures, and the U.S. Government unable to effectively collaborate on data governance with allies.

Furthermore, as a lever in the global competition, the U.S. Government should improve data accessibility throughout the entire U.S. data ecosystem — as data holders, agencies should make their relevant datasets more accessible to the USG and to the private sector, academia, and civil society; as rule-maker, the USG should create restrictions, protections, and incentives to shape behavior around data collection, use, and analysis; and, as trusted convener, the USG should bring together diverse groups to overcome barriers and share data for the public good. There are examples of effective public private partnerships that can bridge USG and non-USG data holdings and access for collective societal and economic benefit. These examples need to be replicated and scaled for various data-related challenges and opportunities in the United States data ecosystem.

Beyond data and on the AI front, we also need to support implementation of the voluntary, consensus-created AI Risk Management Framework (RMF), expected to be released by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in January. The AI RMF should help individuals and organizations inside and outside of the USG improve their ability to map, manage, measure, and govern the management of risk in AI products, services, and systems. In addition, work must continue to determine how best to operationalize the sound principles in the White House’s Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights issued to guide the design, use, and deployment of automated AI systems to protect the American public.

Lastly, the USG must address the threats from PRC platforms operating in the United States, with TikTok being the clearest example (worth noting here is the emergence since September of PRC shopping site Temu as the most downloaded U.S. application). It is not widely known that the TikTok version operating within the United States is vastly different from that offered to PRC users. As Tristan Harris from the Center for Humane Technology recently explained: "In their version of TikTok, if you're under 14 years old, they show you science experiments you can do at home, museum exhibits, patriotism videos and educational videos… and they also limit it to only 40 minutes per day. Now they don't ship that version of TikTok to the rest of the world."

There have been efforts in recent weeks to address the harm caused by TikTok. First, U.S. federal and state governments moved to ban TikTok on government devices. Notably, the U.S. House of Representatives Chief Administrative Officer banned TikTok from all U.S.-House managed devices. Second, Congress introduced legislation banning applications that could be used by adversarial nations to control or surveil Americans. We need to consider two major criteria when evaluating platforms and applications controlled by the PRC or other adversaries, as SCSP noted in our Economy Interim Panel Report. First, national security criteria for assessing whether to restrict or ban certain PRC tech platforms should include factors such as the ownership, control, and management of the tech platforms, the ability of third parties to audit the platform, and the scope and sensitivity of the data being collected by the platform. Second, the United States should also develop additional criteria in response to the lack of reciprocity between U.S and PRC data regulations. PRC data platforms operate freely in the U.S. market while their U.S. counterparts are blocked from China’s market. This lack of reciprocity creates an uneven playing field, depriving American firms growth opportunities through open competition.

Conclusion

I will end this newsletter where I started – Ukraine. What happens in Ukraine will resonate beyond its borders. We know the PRC follows the conflict closely for its considerations over Taiwan. The emerging DemTech model in Ukraine also offers what can be a compelling package of technologies and model of governance as the United States and our allies consider foreign policy priorities for the global tech competition. Ultimately, how we position our economy, military, and intelligence community in the techno-economic competition against China in 2023 will have huge implications for the 2025-2030 timeframe.

SCSP is focused on the 2025-2030 timeframe. Every year between now and then is critical – but perhaps none more so than 2023. And what happens with Ukraine in 2023 and how we position ourselves with regard to China will help determine our posture for the remainder of this decisive decade.